BLACK LIVES MATTER & 21st CENTURY JUSTICE MOVEMENTS

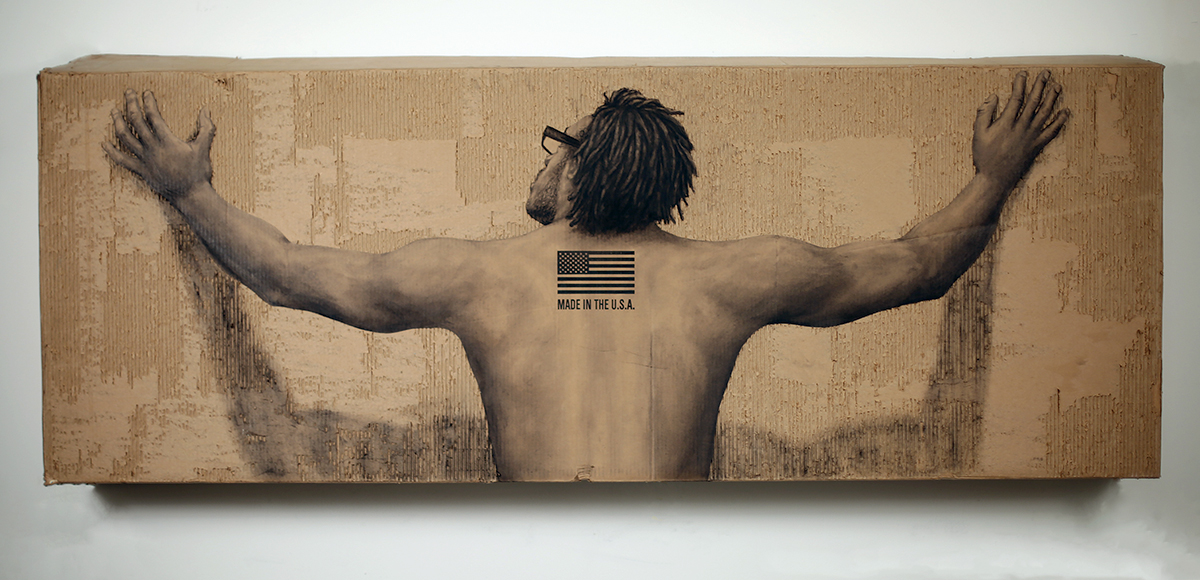

Dareece Walker, "Made in the USA"

Black Lives Matter is the name of a movement begun in the mid-2010s that grew by leaps and bounds in 2020 in the wake of the George Floyd killing to become one of the most massive movements for social justice since the Civil Rights era. Indeed, it may have generated the largest social movement events in US history.

The origins of the Black Lives Matter movement and its subsequent trajectory are complicated, but the story of its naming is clear. In July of 2013, Alicia Garza, a longtime activist and special projects director for the National Domestic Workers Alliance, posted a “love letter to Black people” on Facebook in the wake of the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the man who shot Black teen Trayvon Martin in Florida. She ended the post with “I am surprised at how little Black lives matter.” In response, one of Garza’s good friends, Patrisse Cullors, coined the Twitter hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. The hashtag went viral, and soon Garza, Cullors and a third friend, Opel Tometi, found themselves building the hashtag into an organization. All three women were longtime activists dealing with a range of social issues, including feminist and LGBTQI2+ issues in the black community, as well as poverty, and prison reform.

The hashtag focused concern, anger, frustration, fear and a profound desire for change that had been welling up among African Americans and supporters from other communities at the mounting number of apparent murders of Black men and women by individuals supposedly hired to “serve and protect” all citizens. The Travon Martin verdict was followed by police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York, each of which sparked major waves of protest. Soon the movement brought to public attention the names of dozens of men and women of color who had died at the hands of police officers. The high-profile cases of Martin, Brown and Garner led to the unmasking of a long and bloody history of questionable deaths at the hands of law enforcement. The particularly brutal and video recorded killing of George Floyd in 2020 in the context of a pandemic that disproportionately harmed people of color brought the movement to a new level of consciousness and power.

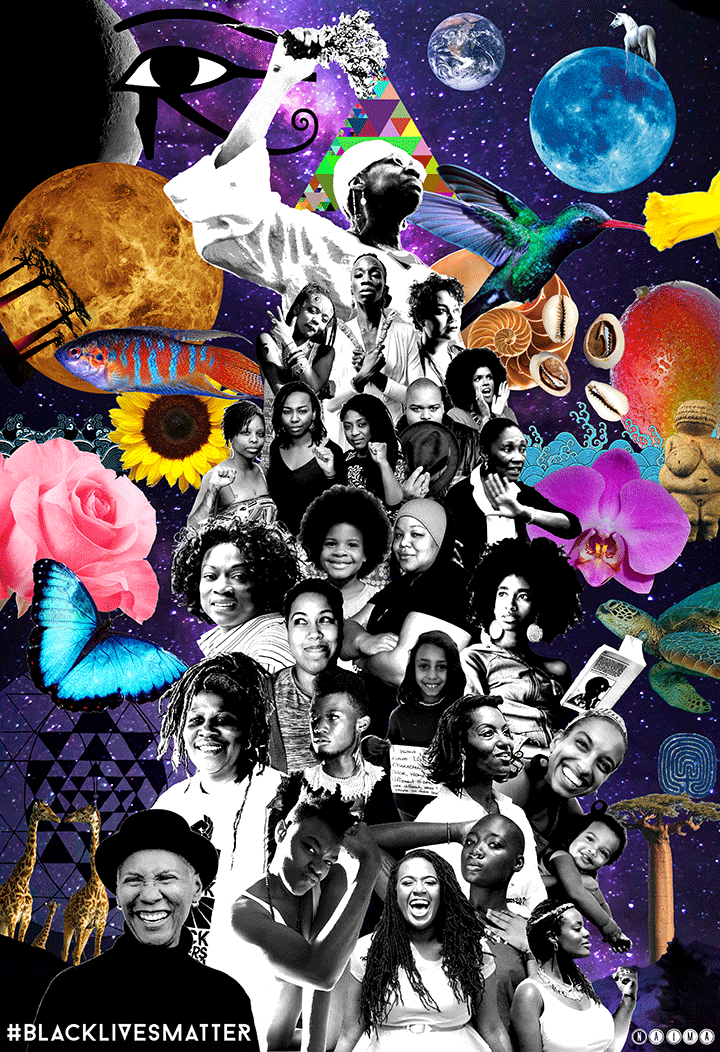

Poster by Naima Penninman

While Black Lives Matter is the name used by many to characterize this new phase of anti-racist struggle, as the co-founders of the #BLM network would be the first to note, the movement quickly grew much bigger than any one organization. Ultimately, the name is less important than the fact that protest quickly evolved into a new phase of a movement that has been going on since the first Africans mutinied on ships carrying them into enslavement in the “new world” in the 1600s. The Movement draws elements from both the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement but is decidedly new and powerfully forward looking.

While the initial focus was on the shooting of unarmed African Americans by police officers, it was clear from the beginning those slayings are part of a much larger set of issues impacting Black lives. Central among these is the mass incarceration of over 2 million Black men and women at rates far, far higher than for whites, including whites who commit the same or similar crimes. African Americans represent about 12% of the US population but make close to 40% of the prison population.

Numerous careful university and government studies demonstrate that these incarceration rates stem in no small part from deep racial biases in the judicial system. Racism in policing agencies at all levels – local, state, and federal – has also been well documented. And this racism seems to have increased rather than decreased in recent years, though it is possible that it is primarily the reporting of these incidents that has increased. One possible factor in the increases may be the conscious strategy of some white supremacists to infiltrate law enforcement. Looking at the larger picture, the movement argues that systematic racism at numerous levels of society has led to the massive amount of poverty impacting African Americans in the US, poverty that in many ways drives the crime statistics. One of every three black American males born today can expect to go to prison in his lifetime. Figures for African American females are also appallingly disproportionate.

To contextualize these numbers, it is crucial to examine what scholars have come to call the Prison Industrial Complex. The term Prison Industrial Complex refers to the logic by which the increasing number of prisoners is driven in part by the increasing profit generated for private corporations associated with the incarceration system. Where prisons were once wholly governmental institutions, first parts of the system, then entire prisons, have been privatized, turned into profit-making entities. And they have been immensely profitable because prison work forces can be exploited as virtually a slave labor force, paid only a small percentage of what would be paid to workers outside of prison. While the percentage of private prisons, as opposed to those run by government, remains small, the complex also includes a whole web of corporations providing medical supplies, food, clothing, and a host of incarceration-related services. Prisons have since the 1990s become a major growth industry, one that can only grow if the number of inmates grows. This has created a hideous incentive to certain corporations to lower costs by decreasing the quality of prison life at the same time that they seek ever more effective ways to exploit prison labor.

The concept is meant to evoke the ways in which the military industrial complex, first warned of by President Eisenhower, drives private defense contractors to push for ever greater military spending not because it is truly needed for our national security, but in order to increase the profits of the corporations who make weapons, planes, tanks, ships and other elements of the military. In a parallel way, the Prison Industrial Complex effectively pushes indirectly and at times directly for an ever-higher prison population to increase their profits. Tied into this logic is a deeply racist system whereby people of color are incarcerated at far higher rates than whites with the tacit understanding that incarcerating non-whites is far more socially acceptable to the dominant white population than would be similar rates of imprisonment for whites. One recent examples of this logic at work is the difference between the criminalizing approach to the crack epidemic in communities of color as compared to the medical approach to the opioid epidemic more associated with white communities. What other than race explains the difference between these two approaches to drug abuse?

The Movement has therefore placed reform of the prison system and its associated criminal justice system at the core if its demands, alongside a demand to the end of police brutality and police-delivered murder, as well as racial profiling and random harassment of men and women of color. The movement recognizes that an entire interlocking system must be addressed. This also includes the fact that mass incarceration of young black and brown men and women significantly contributes to the impoverishment of many communities of color by removing wealth-creating individuals and generating a large number of youths who find themselves unemployable due their record of incarceration.

Many art forms have contributed to the Black Lives Matter movement including perhaps most dramatically rap songs and videos by figures like Beyonce and Kendrick Lamar, among many others.

Some Key Organizations

- Black Lives Matter. Official site of the foundational organization.

- Campaign Zero. Policy-driven approach to ending unjustified police violence. See their excellent Research section for statistical and analytic evidence about which approaches work.

- Ella Baker Center for Human Rights. Excellent folks continuing the work of the great civil rights organizer Ella Baker.

- Mapping Police Violence Documenting cases of death by police across US.

- The Movement for Black Lives. Coalition of several dozen organizations fighting for criminal justice reform and a host of human rights issues.

- #SayHerName. Focused on police violence against Black women, girls & femmes.

Selected Books & Articles

- Alexander, Michele. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2010). Key book about the turning of US prisons into racist, for-profit institutions.

- Austin, Paula et al. "Teaching Black Lives Matter." Radical Teacher 106 (Fall 2016): 13-17.

- Crenshaw, Kimbery, and Andrea J. Ritchie. “Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women.” African American Policy Forum (July 16, 2015).

- Cooper, Bittney. 11 Major misconceptions about the Black Lives Matter movement.

- Dalton, Deron. "The Three Women Behind the Black Lives Matter Movement." Madame Noire (May 4, 2015).

- Davis, Angela Y. Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003). A key text in the creation of the prison-industrial complex analysis.

- Day, Elizabeth. "#BlackLivesMatter: The Birth of a New Civil Rights Movement." The Guardian (July 19, 2015).

- Khan-Cullors, Patrisse. When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2018). The #BLM story from one of its founders.

- Oparah, Julia Chinyere, ed. Global Lockdown: Race, Gender, and the Prison-Industrial Complex (New York: Routledge, 2005). Fine collection of essays.

- Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007). Brilliant book on California's racial injustice system and the wider prison-industrial complex.

- Ransby, Babrara. Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the 21st Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018). Superb placing of BLM in longer history.

- Ransby, Barbara. “The Class Politics of Black Lives Matter." Dissent (Fall 2015): 31-34.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016). Excellent introduction to the #Black Lives Matter network and the wider movement of which it is a part.

- Yancy, George and Judith Butler, “What’s Wrong With ‘All Lives Matter’?

Films, Songs, Videos & Other Black Lives Matter Artwork

- "13th." (2016) Academy Award-winning documentary film directed by Ana DuVernay on the legacy of the 13th Amendment (abolishing slavery) into the current moment.

- "Rest in Power: The Travon Martin Story" (2018) Documentary TV series directed by Jenner Furst & Julia Willoughby Nason.

- "Stay Woke: The Black Lives Matter Movement" (2017) Documentary film directed by Laurens Grant.

- "Say Her Name: The Life & Death of Sandra Bland" (2018) Documentary directed by Kate Davis & David Heilbroner about activist Bland who died after being stopped for a minor traffic violation.

- "Whose Streets?" (2017) Documentary directed by Sabaah Folayon & Damon Davis, on the Michael Brown shooting & BLM.

- 25 songs/videos that embody the Black Lives Matter Movement. Including Kendrick Lamar, Jay Z, Janelle Monae, D'angelo and many, many more.

- Beyonce. "Formation." video and her Super Bowl half-time version.

- Fogg, Victoria A. "The Most Powerful [Visual] Art from the Black Lives Matter Movement." Washington Post (July 13, 2016).