Apocalypse Now and Then:

Bob Dylan’s Endless Engagement with End Times

Señor, señor, do you know where we're headin'?

Lincoln County Road or Armageddon?

From Dylan, “Señor (Tales of Yankee Power)”

It is hardly a revelation to note that over the decades Bob Dylan has been deeply attracted to apocalyptic imagery. As much as any artist of his era, Dylan has presented striking visions of ultimate ends -- personal, political, spiritual and otherwise. These visions and revisions occur and recur, with each repetition at once radically new and full of continuities with earlier musings. Among the ironies anyone looking to Dylan for revelation must face is that he has been a master of disguise throughout his career. I don't know or care if the person going by the name of Bob Dylan has a messiah complex, but I know the messiahs in his songs are complex, as are all the many other apocalyptic elements in them. The apocalyptic imagination that works through so many Dylan songs, moving over time from the literary to the literal and back again, is one key force in weaving together the many layers that give his work such curious power.

Apocalypse in its Greek roots specifically points to the revealing of knowledge, to the uncovering of hidden truth. In that broad sense, virtually the whole of the Dylan canon can be seen as apocalyptic. While the New Testament book “Revelations” is perhaps the most well-known treatment of Apocalypse, in both Jewish and Christian sacred texts there are numerous apocalypses and visions of the End Times (the more common term in Judaic tradition). Some of Dylan’s work certainly resonates with the Apocalypse, the End Times, but that is far from the only kind of apocalyptic imagery in his repertoire. In everyday usage in the Western tradition, the term often refers more generally to any profoundly disrupting event, or catastrophe, whether personal or social. For the purposes of this brief exploration, I want to look at a set of tropes in Dylan’s body of work that speak to various end times and End Times, to seemingly ultimate, if almost always ambiguous, revelations on a number of different planes of existence.

At one level, each of us faces an apocalypse -- the fact that like all living things, our time on earth ends in death, the apocalypse of individual erasure. Death was a much mused upon topic even for the young Dylan and has grown in centrality as he has aged. But there are also many “petite” and not so “petite” deaths within life. Indeed, according to Julia Kristeva in Powers of Horror, “on close inspection, all literature is probably a version of the apocalypse that seems to me rooted, no matter what its sociohistorical conditions might be, on the fragile border (borderline cases) where identities do not exist.”[1] (208) We need not argue that all literature or all Dylan songs follow this trajectory, but certainly these “borderline cases” make up a significant part of the truth for a Nobel laureate whose literary production and career is famous for its shape-shifting dissolutions and transformations of the Self, a trope literalized by Todd Haynes in his film I’m Not There by having six actors, including one woman, play Dylan. As Kristeva suggests, the finality of death can be preceded by various deaths of identity along the way, and few artists have been more chameleon-like, have lived and presented (revealed?) a wider range of selves over time than the agnostic Jewish Christian radical conservative rock blues gospel folk country neo-crooner New York Californian from the North Country of the Midwest.

Beyond the baseline apocalypse of personal existence, and the various apocalypses of selves, one could list additional types or levels of apocalypse in Dylan’s work, ranging from ones that seem primarily political (“Times They Are a Changing,” “When the Ship Comes In”) to the joyful and weirdly comic (“Quinn, the Eskimo” “Highway 61 Revisited”) to the portentously obscure (“All Along the Watchtower,” “This Wheel’s on Fire,” “Dark Eyes”) to the seemingly literal Christian versions from his fundamentalist period (“When He Returns”). But these categories are highly unstable ones. All these songs work on more than one level, and Dylan has also produced a number of even more deeply unclassifiable apocalyptic epics such as “Jokerman,” “Señor,” “Changing of the Guards,” “Not Dark Yet,” “Ain’t Talkin’” and “When the Deal Goes Down.” Dozens of songs could be added in each category.

From Bobby Zimmerman’s Iron Range roots, with cultures of radical unionism set alongside Christian evangelical radio broadcasts, through the political twists of his Guthrie years and the civil rights/folk revival era, to Dylan’s brief but intense mid-career explorations of Judaism and Christianity, to his late in life confrontations with mortality, and with many other transformations along the way, apocalyptic lines run throughout his catalog of several hundred songs. While this list in some ways represents distinct stages in Dylan’s career, and distinct thematic apocalypses, each moment has also built upon and transformed the rest. Each is deeply rooted in his early years and often the thematic levels (personal, political, spiritual) blend in the same song. (While I will argue that these strands cannot by fully separated, throughout the essay I will capitalize Apocalypse or End Times when referencing the specifically Judeo-Christian belief in a Messiah’s return and an ultimate war of Good versus Evil.)

Let me be clear from the outset that my approach will not itself be apocalyptic. That is to say, I do not take the position that the metaphor of apocalypse is the revelatory key to all of Dylan’s work. It is just one of many entry points, and anywhere you start writing about Bob Dylan will lead eventually into web of complexity to which no single approach will do justice. As one of Dylan’s most astute readers, Christopher Ricks, was quick to admit, even such a rich set of tropes as “Dylan’s visions of sin,” laid out magisterially in his book of that title, comes nowhere near exhausting the terrain of Dylan’s hyperactive imagination.[2] And neither does the trope of apocalypse. But tracing end times/End Times allusions in his body of work can be revelatory, can capture something of the particular qualities and elusive complexities of Dylan’s songwriting.

Section I: Roots

Among the sources feeding Dylan’s apocalyptic imagination, five strike me as particularly important:1) the religious traditions of Judaism, Catholicism and Evangelical Protestantism; 2) the revolutionary political apocalypticism of the radical labor movement; 3) Black gospel songs, spirituals and freedom songs; 4) the Romantic/Symbolist poetic traditions of Blake, Whitman, Rimbaud and the Beats; and 5) the Anglo-American tradition of the prophetic Jeremiad with its blend of religious and social proselytizing. These five forces obviously overlap and interplay historically in many different ways in Dylan’s work, balancing, counterbalancing and unbalancing the efforts of any one strand to become dominant.

While religious belief might seem to be the most important among these sources, like so much about Dylan, his “real” religious beliefs are not easily fathomed. And from the perspective of this article, they are not especially relevant since I follow the axiom of D.H. Lawrence, “Never trust the artist. Trust the tale.” In any event, while several books on the subject have illuminated aspects of his religious experience, none convincingly aligns Dylan with a consistent theology.[3] And while taking joker Dylan’s words from any interview too seriously is a mistake, I believe this comment to be more convincing and likely closer to the truth than most:

"Here's the thing with me and the religious thing. This is the flat-out truth: I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don't find it anywhere else. Songs like 'Let Me Rest on a Peaceful Mountain' or 'I Saw the Light'—that's my religion. I don't adhere to rabbis, preachers, evangelists, all of that. I've learned more from the songs than I've learned from any of this kind of entity. The songs are my lexicon. I believe the songs."[4]

The exasperation in Dylan’s voice makes this believable, even as it skips over the fact that he has in fact at times embraced certain rabbis, preachers and evangelists, though only temporarily along his ever-restless journey.

Each of the five sources of apocalypticism outlined above has some grounding in Dylan’s Minnesota roots. To begin with, Judeo-Christian traditions shaped virtually every aspect of life in the young Bobby Zimmerman’s world. His training in rabbinical interpretations of the Old Testament was not insignificant; there was enough of a Jewish community to support a religious Shul (on West 4th in Hibbing) that Bobby attended, and he followed through at least as far as his Bar Mitzvah. At the same time, even as a Jewish boy he was surrounded by dominant Christian influences drawn from the wider town community and the media. There were close to twenty ethnic groups working the mines around Hibbing, and while some of these folks may have exhibited the famous reserve of Midwesterners, others were full of Christian enthusiasm, both Catholic and Protestant.

According to both his own accounts and those of his biographers, Dylan’s formative years seem have been spent huddled close to radios – those lifelines to the wider world in a pre-TV and pre-Internet era. We know how important radio broadcasts were in forming his love for an eclectic variety of music from what has come to be called the great American songbook. In the Dinkytown section of Minneapolis and again in Greenwich Village, Dylan immersed himself in (and at least once stole a copy of) Harry Smith’s deeply influential six-disc Anthology of American Folk Music. That formative era fed a lifelong passion for music collecting that shaped both his own songs and the range evident in his stint as DJ for Theme Time Radio Hour.[5] There is no doubt that as the young Zimmerman spun that radio dial (and since his dad owned an electrical and appliance store he always had a good one), he would have encountered more than a few bits of radio-evangelical religious imagery, and some of them no doubt lodged deep in his extraordinarily agile and absorbent mind. Hellfire and brimstone preachers, then as now, were all over the airwaves. Just as the strange blend of musical offerings from Appalachia, the Deep South and points unknown no doubt proved attractively exotic to a young Minnesota kid’s ears, so too no doubt would the sounds of evangelical Christianity to a young Jewish kid’s. In particular, the Southern radio stations he sought out were full of gospel songs, often blended smoothly with outright preaching, and at least one third of Smith’s folk music anthology consisted of religious songs. Thus, Dylan’s relation to Judeo-Christian apocalyptic imagery is “foundationed deep” (“My Back Pages”) in his childhood. Decades before his brief conversion to fundamentalist Christianity or his later interest in rabbinical studies, biblical imagery fired his imagination.

As for political apocalypse, we know that union culture was also a deep part of the world of northern Minnesota, home to the great Mesabi Iron Range. The Hull-Rust-Mahoning Open Pit iron mine in Hibbing was at the time the largest in the world, and a mural of mine workers was prominent in the High School library. The radically egalitarian cooperative commonwealth vision developed by the Populists, Wobblies and radical miners was carried far into the 20th century, especially by the Farmer-Labor Party in Minnesota. One of Dylan’s social studies teachers at Hibbing High, Charlie Miller, was the local head of the FLP, and he regaled his students with tales of class injustice, especially strike stories and other tales of radical union direct action.[6] The power of that milieu has often been underplayed in discussions of Dylan’s political evolution, but it became an intermittently appearing lodestar of his political imagination, reanimated by Woody Guthrie, and cropping up from the early “North Country Blues” to “Union Sundown” decades later.

Especially during his Guthrie-worshiping years, Dylan re-immersed himself in this musical culture of radical unionism. That vision was itself entangled with certain strands of Evangelical Protestantism, even though often mocked by the Wobblies and Guthrie (see the IWW parody song “Starvation Army”). Yet Guthrie’s song, “Jesus Christ,” an early example of what we would now call liberation theology, explicitly linked radical concern for the poor with Christian tradition. It also happens to be one of the first songs Dylan recorded, on a personal tape player, during his days in the Dinkytown bohemia of Minneapolis. Clearly, Dylan was already deeply aware of radical political strands long before he involved himself in the Civil Rights/New Left of the early sixties. Long before “revolution was in the air” of Greenwich Village, it was lodged in Dylan’s Iron Range imagination, providing a point of contact with what he found later in New York City and the Jim Crow South.

The third strand of apocalypticism to which Dylan is deeply indebted emerges from the great spirituals and gospel songs of the Black tradition. Dylan knew these songs from his radio days, and that set him up to be receptive when he got a strong dose of them through his informal but intense studies among the amateur, professional and performing musicologists of first Dinkytown, then Greenwich Village. Dylan sat in awe of the great Odetta, queen of the interpreters of Black music in the Village scene, and later was as enthralled by the song dreams of Mahalia Jackson as the equally revelatory preacher dreams of Martin Luther King when he stood on the platform in front of the Lincoln Memorial for the most famous gathering of the Civil Rights era. Spirituals and gospel songs are of course deeply steeped in biblical allegory and apocalyptic stories of bondage shattered and justice found in the Promised Land. The already present political, anti-slavery allegory in these songs was reinforced and extended powerfully and topically through the great Freedom Songs adopted and adapted for the Civil Rights movement. The organized voice of that movement’s liberation musicology, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s (SNCC) Freedom Singers, shared the bill with Dylan on more than one occasion. Their greatest singer, Bernice Johnson Reagon, has spoken of Dylan’s influence on her, though surely Dylan was in turn influenced by this tradition.[7]

The fourth key source of Dylan’s affinity for images of end times and radical transformation, the Romantic literary tradition, also had roots in his childhood. Ginsberg and the Beats are often credited with nourishing Dylan’s interest in this tradition and in the Symbolist poets, but we also know that his Hibbing High English teacher, B.J. Rolfzen, was a formidable and inspiring early influence. Apparently, Bobby “Zimmy” Zimmerman always sat in the front row of Rolfzen’s 10th grade English class, and according to one student, Rolfzen was a magical teacher “who loved poetry, and preached poetry almost like a religion."[8]

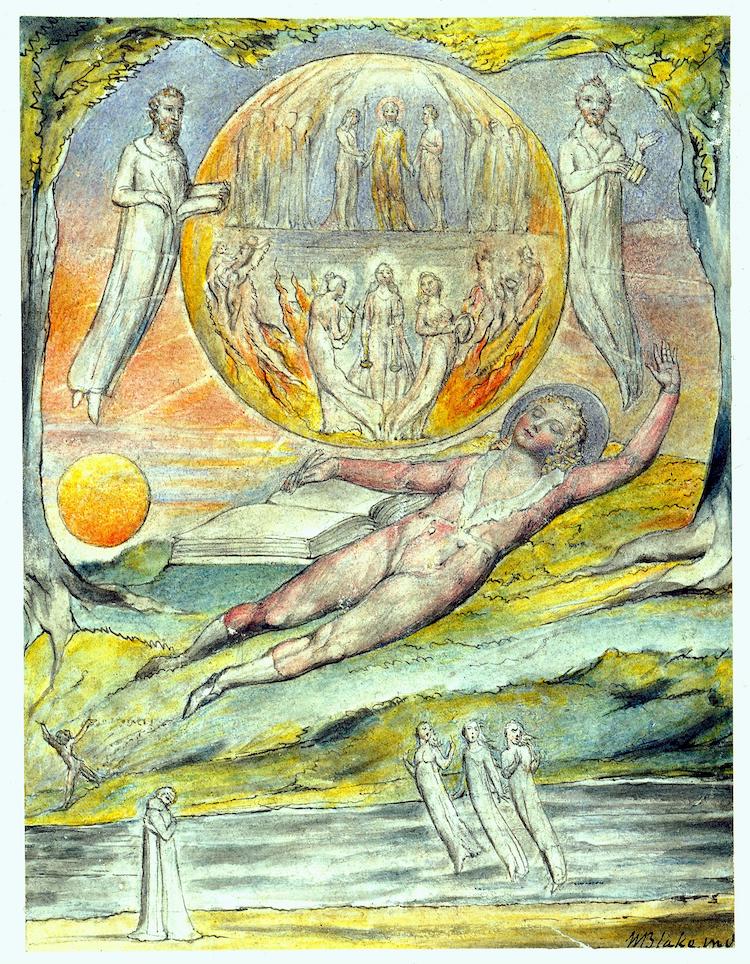

"The Youthful Poet's Dream," by William Blake

Of the many poetic influences Dylan absorbed in his early years, his immersion in William Blake in particular would have exposed him to an extremely rich and varied set of apocalyptic images and positionings. Blake’s profoundly original and idiosyncratically heretical revisions of Christianity, tied as they were to an equally radical politics, provided Dylan with a model of both how to appropriate and revise biblical notions and visions of apocalypse, and link them to psychological and political transformation. In turn, Walt Whitman’s “democratic vistas” tied such visions to the specific terrain of Dylan’s native land, settled it into the American grain.

The fifth and final strand is less a separate one than one that is woven throughout the other four. The Jeremiad has a rich tradition in Anglo-American and African American culture, beginning with the sermon “A Model of Christian Charity,” delivered by John Winthrop on the Arabella as it sailed toward Massachusetts Bay to set up a colony there, though the tradition has far deeper Judeo-Christian roots. The American version of these sermons, named after the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah, work by setting up a social ideal (based initially on biblical utopias but later secularized), chastising the populace for falling short of that ideal, and calling forth an effort of rededication to a “new world” (religious but also political, or cultural). Moving out from its sermonic New England roots, the Jeremiad became ubiquitous in American political, social and aesthetic discourse. A parallel counter tradition later emerged from the syncretic Christianity born in slavery. Both these strands found their way into the fabric of popular culture and everyday life, especially through song and through the poetic tradition founded by Whitman and carried through to Dylan’s contemporary and friend, Allen Ginsberg. This style of discourse became a central part of American civil religion, a key form for articulating the American dream of stepping outside of history to fulfill some revealed City upon a Hill, some Democratic Vista, one or another Destiny to be made manifest.[9] As in Dylan’s work, it is often difficult to tell whether the promised land will be on earth, or only in Heaven, but all four of the other strands of the apocalyptic in Dylan’s world are shot through with elements of the Jeremiad tradition. Whether idealistically in “When the Ship Comes In,” vitriolically in “Masters of War,” or satirically in “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” the Jeremiad echoes throughout his body of work.

Over the years Dylan’s lyrical and musical genius has woven countless rich and varied tapestries of rhyme from these five strands. While it is partly true that Dylan is “an artist who, in drawing on multiple religious traditions and attitudes, yokes them together by means of a marvelously syncretic imagination,”[10] “syncretic” makes the process sound far more orderly than it is in the actual body of work. Both the overlaps and the disjunctions of various kinds of apocalypticism play crucial roles in forming the landscapes and soundscapes of Dylan’s world.

Section II: Branches

In addition to poking some fun at the pretensions of a certain Francis Ford Coppola film, the phrase “apocalypse now and then” in my title is meant to suggest that apocalyptic ideas and images come and go in Dylan, with varying degrees of centrality and seriousness. The extent to which Dylan makes those ideas and images central to his aesthetic and cultural project varies not only over time but also within any given album or song. Typically, in the context of an album, the apocalyptic strain is tempered by more mundane fare, most often love songs and other lighter fare. Think, for example, of the two sides of the John Wesley Harding album. The A-side and parts of the B-side are as full of portentous apocalyptic moments as any album in Dylan’s career, including his evangelical Christian period.[11] Songs like “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine," "Drifter's Escape," "The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest,” “Dear Landlord,” and of course "All Along the Watchtower,” are redolent with revelation, if decidedly oblique ones. By contrast, the B-side ends with the ostensibly plainspoken love songs “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” and “Down Along the Cove,” songs that presage the mellow country Bob of Nashville Skyline and seem far removed from End Times concerns. But such a division of planes between the spiritual and the mundane has not always been typical of Dylan’s work, and many of his love songs (“Dark Eyes,” “One More Cup of Coffee”) contain apocalyptic echoes, and his apocalyptic songs often connect to failed relationships (“Things Have Changed”).

Any attempt to create a typology of Dylan’s apocalyptic moments will also encounter a typically slippery set of tropes and tricks. Indeed, typology itself, in biblical hermeneutics, is one of the signs of apocalypse, or rather the master code for anticipating Armageddon. Through much of the Judeo-Christian era, apocalyptic revelations were at most the end of a time, an era, not necessarily the End of All Time. In both Jewish and Christian biblical exegesis there are traditions speaking of no fewer than four levels of meaning in any biblical passage, an approach that clearly resonates with Dylan’s use of apocalyptic ideas and images. Jewish tradition speaks of Peshat (simple, literal) Rehmez (intimation) Dehrash (conceptual) and Sud (hidden, mystical). For Christianity these levels are the literal, the allegorical, the moral, and the eschatological. Take, for instance, the word Jerusalem as it appears in a biblical passage. On the literal level it refers to the historical city itself; allegorically, it is said to represent to the church of Christ; morally, it points to the city-state of the human soul; and eschatologically it points to the heavenly Jerusalem that will rise at the End of Time-- the moment of the ultimate Apocalypse. Dylan would have encountered this complex interpretive schema through his studies over the years, but with or without such conscious knowledge his imagination seems to have had an intuitive grasp of this kind of multilayered discourse, one reason for the enigmatic nature of much of his work.

This helps explain why any typology seeking to neatly parse out the categories of Dylan’s apocalyptic imaginings will prove reductive and will quickly founder on the evidence that the various types or levels have been fused, confused or refused as separable moments. Any such typology of Dylan’s apocalypses would need to account for both the deadly serious and the outrageously funny, and would need to deal with interweavings of psychological, religious, political, and cultural levels. As is usual with Dylan’s work, as soon as one tries to sort out such levels, it becomes clear that to do so is an impossible mission and deeply wrong-headed. The multiple layers and deep ambiguities are a large part what makes much of Dylan’s work inhabitable, gives the sense that you can immerse yourself in the cityscapes, Jerusalem or otherwise, of his imagination. In other words, much of the power of Dylan’s use of ideas and images of end times/End Times comes from the commingling of personal, prophetic, and political in the same song. It is why, for example, that the song chosen to represent his work at the Nobel Prize ceremony, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” can be about both nuclear war and Armageddon, and can also echo today with the climate crisis. It is also why the señor in “Señor” can be a guy in a cantina and the Lord, since el Señor is His name in Spanish. Ambiguity is at the heart of Dylan’s apocalypticism in a host of songs. Who is the “Jokerman”? What is changing in “The Changing of the Guard”? Where on Earth or in Heaven are those “Highlands”? Why are those “Wheels on Fire”? Even his purest political protest songs are shot through with biblical references, while at his seemingly most literal in his so-called “born again” phase (a term Dylan intensely dislikes), the revelations of End Times are full of secular references and seldom seem confined to one plane of existence. How different is that “Slow Train” from the earlier mail train where the singer “can’t buy a thrill” as wintertime approaches?

Playing with the notion of four levels, we might, somewhat perversely, offer a mixed-up list that would look something like this: the literal Judeo-Christian End Times/Apocalypse (the lowest level); the personal level of psycho-social transformation; the political level of revolutionary change; and what I’ll call the “mystery train” level where “nothing is revealed” but much is promised.

Where apocalypse recently has often meant the terrible reductionism of fundamentalism (as manifest in works like Tim LaHaye’s “Left Behind” series of End Times fiction), apocalypse for Dylan has almost always been riddled with ambivalence and complexity. Biblical exegesis will only take us so far into Dylan’s songscapes. Even during his so-called born again phase, when he embraced the imminent historical arrival of Armageddon as predicted in Hal Lindsey’s Late Great Planet Earth, his visions were complicated by his hyperactive imagination.[12] In this he is far closer than current evangelicals to biblical sources. The most thorough resource on the apocalypse is St. John’s Book of Revelations, so much so that it is sometimes mistranslated as the Book of Apocalypse. It is also widely regarded as the Bible’s most obscure chapter. The book is rife with strange beasts, and enough portents and darkly ambiguous images to please the most obscure Symbolist poet (or Minnesotan song and dance man).[13]

Any attempt at historical reductionism will likewise falter quickly. It is both necessary and insufficient to historicize Dylan’s evocations of apocalypse. While taking note of the historical contexts of his various plays on end times is at points crucial, it will never tell the whole story because Dylan’s sense of time moves between the linear and the cyclical, and of course because many of his songs are rewritten into the script of new times. Early sixties songs like “Hard Rain,” “Chimes of Freedom,” “Let Me Die in My Footsteps,” and “Masters of War,” are obviously shot through with bomb angst and images of the nuclear threat. One of the most astute writers about Dylan’s politics, Mark Marqusee, argues that “in Dylan’s work of the sixties apocalypse is a social category.”[14] Certainly that was more true in that decade than ever after, but it’s not the whole truth. On the one hand, Dylan has periodically returned to political screeds throughout his career. And on the other hand, as the great Wobbly song interpreter Utah Phillips used to point out, there is considerable distance between an IWW song with the line “dump the bosses off your back,” and “how many seas must a white dove sail before she sleeps in the sand.” Moreover, all one has to do is listen to Mavis Staples sing “A Hard Rain” in rocking gospel style in Martin Scorsese’s Dylan documentary, No Direction Home, to feel that deep biblical connections were always more than just a vehicle for social protest in Dylan’s vision. On the other hand, while “Masters of War” keeps being made timely by the bellicose policies of the US government (his performances of the song were chillingly resonant on the eve of the War in Iraq, for example), the song also clearly retains unmistakable links to the sixties antiwar movements that helped midwife it, as does a late sixties song like “I Pity the Poor Immigrant,” a figure who to me anticipates the My Lai massacre, a military immigrant “Who tramples through the mud/Who fills his mouth with laughing/And who builds his town with blood.”[15]

As with religion or pretty much any other aspect of life, anyone seeking consistency in Dylan’s political views is unlikely to find satisfaction. Dylan encountered elements of Midwest Populism and radical unionism, Guthrie’s grassroots communism and civil rights/anti-war politics in the sixties and later briefly flirted with Zionism, but none of these led him into systematic ideology or any political party. But his work has often been profoundly political, and not just in his so-called protest songs. Acute analyses like his brilliantly condensed take on the class politics of racism in “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” or his hilarious takedown in “John Birch Society Blues” of the kind of conspiracy theories that are once again fueling right-wing American paranoia, are somewhat rare but often powerful. Apart from overtly political interventions, there is also a level of what we might call existential politics in many of his putatively post-protest songs. As Marqusee writes, “It’s Alright Ma is filled with a Gramscian conviction that the most insidious means of domination are those that secure the ‘spontaneous consent’ of the dominated. It’s a song about ‘the mind-forged manacles’ that Blake heard clanging as he walked the streets of London in 1792.”[16] Dylan’s nineteen-sixties symbolist/surrealist era is shot through with an existential politics that is at once political and personal. Dylan’s sense of justice generally has had either a deeply individual focus (“Hattie Carroll,” “Emmett Till,” “Hurricane”), or a highly abstract quality, the latter often sung in apocalyptic tones. In the apocalyptic political songs (“Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Times They are A’changin’”, “A Hard Rain,” “Chimes of Freedom,” etc.) his sense of justice is so intense and his sense of the inevitable duplicity of all ideologies so deep, that only a total Revelatory Revolution can embody his political desire. That is why it often seems that for Dylan the only justice he can imagine is divine justice, apocalyptic justice.

As for the level of personal/psychological apocalypse, Dylan songs have often chronicled that “fragile border” of identities Kristeva found central to the literary imagination. In addition to the deaths of various identities well chronicled in his career, many of these apocalyptic moments are tangled up with the death of relationships. Probably the most spectacular of these break ups is the bitter end of his first marriage as recorded most fully in Blood on the Tracks, but referenced often in later works, including the unique direct address to “Sara” on Desire. Other women and men also face dramatic end times in Dylan’s imagination. For “those who think death’s honesty won’t fall upon them naturally” life must not only get “lonely” but frightening, with ultimate judgment seeming just around the corner for Baby Blue, Miss Lonely, and Mr. Jones. And sometimes, especially after the late sixties, one judgmental finger is always pointed back at the narrator, who may or may not be Bobby, Zimmy, or whatever you wish to call the songwriter. In his many revenge songs, revelations of radical changes of mind and heart are rendered with a depth somehow beyond the specific occasion or object. There is that “Idiot Wind” blowing not only through marital dissolution but seemingly across the whole world; that “mail train” baby where no thrill can be bought; that empty tomb at the end of the road in “Isis;” that release so high above those prison walls; those “Dark Eyes” that haunt like visions of Johanna; the “everything” that is going to be different once the narrator paints that masterpiece or when Quinn the Eskimo arrives. These songs have transitionary borders with portents that seem to go beyond the singular, the personal. They speak to apocalyptic moments in all our lives. Calling these songs “personal” is at best a partial truth. And what does “personal” even mean in an artist who wears so many masks, has so many personae, an artist so deeply invested in mystery trains and mysterious refrains.

So, if we resist seductive but reductive attempts to sort out and create a typology of Dylan’s use of apocalyptic images and themes, what are we left with? With Bob Dylan songs. My category “mystery train” songs points toward that “old weird America” where these layers of meaning co-exist, where the personal is the political is the spiritual.[17] Songs that acknowledge that we “become our enemies the most that we preach” (“My Back Pages”). Songs that, at their best, always have their “five believers” hidden among “fifteen jugglers” (see “Obvious Five Believers”). Dylan’s skeleton keys are seemingly rattle near to death’s door, constantly remind us that that door is never far away (our end time, like it or not, will be at hand one day). But his favorite keys have always been musical ones (including Alicia Keys in one song), and in that there is always the distant, echoing possibility of Redemption, even as we go into the valley below.

Many of Dylan’s apocalyptic sources are obscure enough in their own right, but even that most puzzling of biblical books, St. John’s “Revelations,” is apparently not obscure enough for the Bard of Rock. A strand of twisted and tortured allusions to arguably the most elusively allusive of the gospels runs throughout Dylan’s work, including on Rough and Rowdy Ways, the album released on the cusp of his eightieth year on the planet. It is an album as full of apocalyptic moments as any the songwriter has ever produced. In “My Own Version of You,” for example, a bizarre revision of the Frankenstein story, also includes a phrase in which St. John is compared to Liberace and Leon Russell.

I’m gon’ make you play the piano like Leon Russell

Like Liberace, like St. John the Apostle

I’ll play every number that I can play

I’ll see you maybe on Judgment Day

After midnight, if you still wanna meet

I’ll be in Black Horse Tavern on Armageddon Street

While having St. John playing piano in a dive bar may be the most bizarre riff in Dylan’s apocalyptic repertoire, it is no more obscure than the references fifty years earlier in “All Along the Watchtower.” Arguably Dylan’s most condensed take on end times, its four short verses manage to draw images from not only Revelations, but Isaiah and Ecclesiastes as well. But once again, Dylan’s use and abuse of those already murky biblical sources seems to further complicate any clarity that one might have fathomed from them. While in tone “Watchtower” is perhaps even more ominously apocalyptic than such songs from his evangelical phase as “Slow Train Coming,” and even more ominous in the Jimi Hendrix version Dylan later adopted, it is far from clear just what smooth or rough beast is slouching toward Bethlehem or Jerusalem or wherever that watchtower is located. Surely some reckoning is at hand, and yet, as another song on the same album notes, “nothing is revealed.” Half a century later in another song on Rough and Rowdy Ways, “Key West,” the narrator is still playing “both sides against the middle/Trying to pick up that pirate radio signal,” still looking for “immortality,” just in a different key.

Dylan’s repertoire of apocalyptic tunes is such that his later songs sometime self-referentially rewrite apocalyptic moments in earlier ones. “Jokerman,” for example, the first great end times song after the end of his period of evangelical rapture, is riddled with allusions to “Watchtower,” “Tambourine Man” and other of his earlier assays into revelatory moments. The joker in “Jokerman” may be akin to the joker near the watchtower, a joker who may be hanging as Christ did next to a thief as he had his “moment of doubt and pain” (as those “bad boys the Rolling Stones” phrased it). The Jokerman seems to be another very unorthodox Christlike figure who is somehow merged with a Cretan goddess: “You were born with a snake in both of your fists while a hurricane was blowing/Freedom just around the corner for you/But with truth so far off, what good will it do?” Good question. In some ways, the Jokerman combines into himself both the cynicism and the reassurance of “Watchtower’s” odd couple, and as in so many Dylan songs, it appears also to be and not to be about the songwriter himself. (If Dylan has a “messiah complex,” as some have claimed, that is far less interesting than the complexity of the messiah images in his songs.) The earlier joker complains of businessmen who drink his wine and plowmen who dig his earth without comprehending any higher truth. But the thief assures him that it is not “our fate” to “feel that life is but a joke.” But then, what truth is at hand as the “hour is getting late”? Seemingly, no song ends on a more fateful and daunting note than the one where “two riders are approaching, and the wind begins to howl,” yet those riders are unnamed and once again the allegory is far from revelatory.

And maybe Bob has a joke even in that seemingly fatalistic closing line. Maybe we are meant to hear “riders” as “writers,” and maybe his pen is mightier than the swords of the biblical horsemen. Certainly, in Dylan not much is really sacred, not even his extravagantly praised lyrics and the ending of one of his most resolutely apocalyptic songs. Michael Gray tells us that “Watchtower” is the most performed text in Dylan’s repertoire, with over 2250 performances by 2021, according to the official Bob Dylan website. More interestingly, Gray notes that quite often Bob has sung another version that is significantly different from the original. In one of Dylan’s many lyrical revisions in live performance, the seemingly apocalyptic moment in “Watchtower” turns cyclical, circles back to end on a more open plaint: “There must be some way out of here.” This seems to take the burden of judgment off the Great Decider in the Sky, or those unnamed rider/writers, and puts it back on the audience who must find their own way, if they “know what any of it is worth.”

Dylan can ask these questions honorably because at least since the days of John Wesley Harding, he puts himself among the fools, thieves, idiot blowhards and sinners. (The Jokerman too is a “Manipulator of crowds, [and] a dream twister.”) To give another example, Dylan seems to play with his own portentous arrogance in “Watchtower” in the darkly comic, “Señor, Tales of Yankee Power.” The opening lines mock the solemnity of “Watchtower,” even as the tone has its own ominous seriousness. “Señor, señor, can you tell me where we’re headin’/ Lincoln County Road or Armageddon?/ Seems like I’ve been down this road before/ Is there any truth in that, Señor?” In a manner reminiscent of “Dear Landlord,” the play on the Spanish name for the Lord, Señor, has a way of mildly undercutting the apostrophic gesture of invoking God’s name. Seems like I’ve been down this road before nicely mocks Dylan’s own, by now I fear much belabored, fascination with end times. And when the speaker asks, “Is there any truth in that, Señor?” he sounds an awful lot like the Joker, with no reassuring Thief to offer a less cynical reading. In this tale of Yankee power (mocking at once perhaps the faux spiritualism of Carlos Castaneda’s forged Yaqui Way of knowledge and US imperialisms of all kinds), the end echoes the joker’s questions, and the impatient “Can you tell me what we’re waiting for, Señor?” sounds a blasphemous note closer to despairful ennui than a big bang of Revelation or Revolution. And note the qualifier two decades later in the most explicit of the apocalyptic moments in “Things Have Changed” : “if the Bible is right, the world will explode.”

As always in Dylan, questions are far more important than answers, however hopefully or hopelessly proffered. “Is there any truth in that?” and “Can you tell me what we’re waiting for?” keep questions alive even amidst a sickness unto death. Is it the Messiah, Jokerman or Quinn the Eskimo, Highway 61, Lincoln Country Road or Armageddon?

Though often lauded for his “topical songs,” these make up only a small part of his repertoire, and even the most seemingly topical of those songs often open out to a timeless dimension. Throughout his career Dylan’s eye has focused on eternity and eternal questions. I have purposely avoided a chronological treatment of these apocalypse songs because they themselves invariably fuse and confuse timeframes, redolent with allusions from very different historical eras. What has remained constant is an obsession with end times, an obsession that serves again and again to take mundane time out of our minds, an obsession that asks us again and again to look beyond our present moment. Without ever telling us what to think or precisely how to think about it, they call us to talk more profoundly about of lives, to “not talk falsely” because always “the hour is getting late.”

Blessedly, most Dylan albums also offer up some respite from this obsession. One Dylan song where apocalyptic thinking is specifically challenged, if not ultimately rejected, is “Shelter from the Storm.” That song contains a voice that seems to mock the gloom of end times thinking. The “she” in the song seems to offer a loving alternative to this particular obsession. She takes away his “crown of thorns,” and responds to the apocalypse monger with a different point of view.

Well, the deputy walks on hard nails

And the preacher rides a mount

But nothing really matters much

It’s doom alone that counts

And the one-eyed undertaker

He blows a futile horn.

“Come in,” she said, “I’ll give ya’

Shelter from the storm.”

Well, I’m livin’ in a foreign country but I’m bound to cross the line

Beauty walks a razor’s edge, someday I’ll make it mine

If I could only turn back the clock to when God and her were born

“Come in,” she said, “I’ll give ya’

Shelter from the storm.”

Granted, by the end of the song the singer is ambivalent about the “fatal dose” of “salvation” the “she” of the song offers up, but still he wishes to get back to when “God and her were born,” back to the place of shelter from the storm. This is in many ways a reprise of the end of the John Wesley Harding album in which two love songs follow upon a series of disturbingly inconclusive narratives of despair and foreboding. And most other Dylan albums offer a similar return to the quotidian at or near their end. Blonde on Blonde, for example, after a dozen songs of desolation, despair, vicious put downs and eternal longing, ends with “Sad-eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” where the judgmental voice gives way to a plaintive call for the “lady” to accept the gifts he leaves at her gate.

Section III: Leavings

Bob Dylan has long been a disappointment to ideological purists, and, apart from his brief flirtation with fundamentalism, a disappointment to religious purists. That perhaps has been his saving grace, a refusal of easy categories and complacent positionings. Dylan songs never let purists, or any of us, feel comfortable in our beliefs, beliefs about the world, about ourselves or about Ultimate Ends. Apocalyticism can be highly dangerous, can be a source of terrorism and other forms of fanaticism. What the person whose passport says “Robert Dylan” believes about End Times or Armageddon is not our concern. That guy might be a “False Prophet.” But the “Mother of Muses” offers something else. At their best, the apocalyptic songs Dylan’s muse has given call us again and again to question any total erasure of sin, of doubt, of pain. In one of Dylan’s less well known songs, “Obviously Five Believers,” on Blonde on Blonde (1966), there is a lyric that goes, “fifteen jugglers, fifteen jugglers/ five believers, five believers.” To me that sums up the best approach to Dylan songs, especially the most deeply apocalyptic of them. The five believers are always hidden among fifteen jugglers. That structure undermines, even as it evokes, our desire for revelatory belief. In an era of dangerously fierce partisanship, that questioning may be something each of us needs to embrace more fully.

We are living, once again, in apocalyptic times. There is a frightening battle in progress between those seeking desperately to head off an environmental and political apocalypse, and those happy to rush headlong into a series of disasters they believe portend the End Times. While some try to connect Dylan only to this latter tale, as one astute critic has noted, amidst a deeply dark meditation on US history, Dylan’s latest album offers a litany of figures known for fighting against racism and fascism, figures including fellow musicians Woody Guthrie, Nina Simone, Sam Cooke, and Joan Baez.[18] Whether “the ship comes in” or gets sunk by “the flood coming down” remains an open question. It is a profound, democratic question, one rooted deep in the great American song book and rearticulated with peculiar brilliance in Bob Dylan’s greatest songs.

Notes

[1] Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (Columbia UP, 1982): 207.

[2] Christopher Ricks, Dylan’s Visions of Sin (Harper Collins, 2003).

[3] Among these books, Scott Marshall’s Bob Dylan: A Spiritual Life (BP Books, 2017) is the most comprehensive, but is clearly marred by a defensive desire to prove Dylan remained centrally Christian after his overt fundamentalist phase. There certainly are many lines in Dylan’s later works, after his move away from a specific evangelical sect, that seem to refer quite directly to the End Times. But in this piece, I am more interested in the literary rather than the possible literal meaning of these allusions.

[4] David Gates, “Dylan Revisited,” (October 5, 1997). https://www.newsweek.com/dylan-revisited-174056

[5] These rich radio broadcasts from 2006-09 are archived at http://www.themetimeradio.com/

[6] On Dylan’s high school years as a source for his social and musical vision, see Greil Marcus, “Hibbing High School and ‘the Mystery of Democracy,’” in Highway 61 Revisited: Bob Dylan’s Road from Minnesota to the World, ed. Colleen J. Sheehy and Thomas Swiss. (U of Minnesota P, 2009), 3-14.

[7] See T.V. Reed, The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle. (U of Minnesota P, 2019), especially chapter 1.

[8] Dan Kraker, “The Hibbing High School Teacher Who Mentored Bob Dylan,” MPRNews (October 13, 2016), online at https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/10/13/bob-dylan-hibbing-english-teacher-mentor-nobel-prize-literature. Greil Marcus offers similar praise for Dylan’s teacher in his “Hibbing High” essay.

[9] On the history of these prophetic strands, see Sacvan Bercovitch, The American Jeremiad (U of Wisconsin P, 1978), David Howard-Pitney, The African American Jeremiad (Temple UP, 2005), and David W. Noble, “The American Jeremiad Twice Revisited.” American Quarterly 59/1 (March 2007): 191-197. From a more musicological and Dylan-centric angle, see Greil Marcus, The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes (Picador, 2001).

[10] R. Clifton Spargo and Anne E. Ream, “Bob Dylan and Religion,” in The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan, ed. Kevin J. Dettmar (Cambridge UP, 2009), 88.

[11] Clinton Heylin claims to have found more than sixty biblical allusions on the album, and quotes Dylan’s mom Beatty as remembering that Bob had a huge Bible on a wooden stand near where he was composing. Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 284-89.

[12] Dylan apparently discussed Lindsay’s book with singer Maria Muldaur, an old friend and fellow convert. In 1979, he clearly believed the End Times would soon be at hand, with the wars in the Middle East as evidence of this. The extent to which Dylan continued to believe this in subsequent decades unclear. The conversation with Muldaur and Bob’s belief that Armageddon was nigh in these years are discussed in Howard Soanes, Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan (Grove Press, 2021), chapter 8, “Faith.” Christopher Ricks notes the important difference between Dylan the proselytizer and Dylan the artist: “Even songs of conversion … are converted by him from faith healing to art healing.” Dylan’s Visions, Kindle, p. 1358.

[13] In a personal communication at a Dylan conference in Minneapolis (2007), rock critic Dave Marsh bitterly called Revelations a thoroughly fascist text, which it surely has been in certain readings. But it is also a text as multitextured as Dylan’s most impenetrable songs. Parts of that conference were turned into essays published as Highway 61 Revisited: Bob Dylan’s Road from Minnesota to the World (U of Minnesota P, 2009), ed. Colleen J. Sheehy and Thomas Swiss.

[14] Mark Marqusee, Chimes of Freedom: The Politics of Bob Dylan’s Art (New Press, 2003).

[15] Critic John Landau, in his review of John Wesley Harding, sees the war as pervading the entire atmosphere of the album despite never being mentioned. Landau, “Review of John Wesley Harding,” in Bob Dylan: The Early Years, ed. Craig McGregor (Da Capo Press, 1990), 260.

[16] Cited in Stefan Schindler, “Chimes of Freedom: The Politics of Bob Dylan,” Political Animal Magazine (October 14, 2016). https://www.politicalanimalmagazine.com/2016/10/14/chimes-of-freedom/

[17] The terms “mystery train” and “old weird America” are explored by Greil Marcus in his books with those titles. I use them here to suggest both the particular strangeness of Dylan’s style and the fact that some of that strangeness is present in songs going back hundreds of years.

17 This is the view of Drew Warrick in his review of Rough and Rowdy ways: “Almost every figure Dylan namedrops on Rough and Rowdy Ways is an enemy of tyranny. There’s General Patton, who smashed the Nazi war machine on the European front; Anne Frank, whose hopeful diary, written under Nazi occupation, is a classic; Indiana Jones, who once shoved a Nazi into a spinning airplane propeller. In ‘Murder Most Foul,’ Dylan hones in on musicians who have waged war against oppression. Sam Cooke sang ‘A’ Change is Gonna Come.’ Nina Simone demanded ‘Just give me my equality!’ Joan Baez said ‘And we're still marching on the streets, with little victories and big defeats, but there is joy, and there is hope and there's a place for you!’ Woody Guthrie promised to ‘Tear Them Fascists Down.’” Warrick, “Bob Dylan: Love and Violence in the End Times,” Michigan Daily (June 24, 2020).

https://www.michigandaily.com/music/bob-dylan-2020-love-and-violence-end-times/

References:

Bercovitch, Sacvan. The American Jeremiad. U of Wisconsin P, 1978.

Gates, Dave. "'Full-on Rave' for Dylan Film," Newsweek (November 7, 2007). https://www.newsweek.com/full-rave-dylan-film-96961

Gray. Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. Continuum, 2006.

Griffey, Adam Clay. “Dylan’s Apocalypse: Country Music and the End of the World,” MA thesis, Appalachian State University, 2011.

Heylin, Clinton. Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited. Harper Entertainment, 2003.

Howard-Pitney, David. The African American Jeremiad: Appeals for Justice in America. Temple UP, 2005.

Kraker, Dan. “The Hibbing High School Teacher who Mentored Bob Dylan,” MPRNews (October 13, 2016). https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/10/13/bob-dylan-hibbing-english-teacher-mentor-nobel-prize-literature.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Columbia UP, 1982.

Landau, John. “Review of John Wesley Harding.” In Bob Dylan: The Early Years, edited by Craig McGregor, 248-64. Da Capo Press, 1990).

Marcus, Greil. The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes. Picador, 2001 (also published under the title Invisible Republic).

Marqusee, Mark. Chimes of Freedom: The Politics of Bob Dylan’s Art. New Press, 2003.

Marsh, Dave. “Message from Bob Dylan: A Direction Home.” Counterpunch (October 1, 2005). http://www.counterpunch.org/marsh10012005.html.

Marsh, Dave. Personal communication at the “Highway 61 Revisited” conference, Minneapolis, March 26, 2007.

Marshall, Scott. Bob Dylan: A Spiritual Life (BP Books, 2017).

Noble, David W. “The American Jeremiad Twice Revisited.” American Quarterly 59, no.1 (March 2007): 191-197.

Reed, T.V. The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle. U of Minnesota P, 2019.

Ricks, Christopher. Dylan’s Vision of Sin. Harper Collins, 2003.

Schindler, Stephan. “Chimes of Freedom: The Politics of Bob Dylan,” Political Animal Magazine (October 14, 2016). https://www.politicalanimalmagazine.com/2016/10/14/chimes-of-freedom/

Soanes, Howard. Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan. Grove Press, 2021

Sheehy, Colleen J. and Thomas Swiss, eds. Highway 61 Revisited Bob Dylan’s Road from Minnesota to the World. U of Minnesota P, 2009.

Spargo, R. Clifton and Anne E. Ream, “Bob Dylan and Religion,” in The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan. Edited by Kevin J. Dettmar, 87-99. Cambridge UP, 2009.

Warrick, Drew. “Bob Dylan: Love and Violence in the End Times,” Michigan Daily (June 24, 2020).

https://www.michigandaily.com/music/bob-dylan-2020-love-and-violence-end-times/