Peace Signs: Comparing Anti-War Posters

From the Vietnam War and the Gulf Wars

Copyright 2006; 2019 by T.V. Reed. Originally published online in 2006. Revised 2019.

Figure 1. Weisser, 1967. Courtesy of Sixties Project.

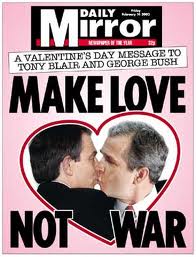

Figure 2. 2003. Courtesy of LeDoigt.

Two posters, forty years apart, with the same words but different images and very different contexts. Does the recurrence of the "make love, not war" theme suggest that peace is just a dream, a fantasy? Or does the parallel just tell us that some political leaders cannot learn from history? Or does it tell us something else entirely?

This chapter will sort through these and other questions as it examines some of the similarities and differences between the Vietnam era peace movement (1965–75), and the movement against the invasion and occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan (2003–?).

As Figure 3 suggests, many in the Iraq peace movement quickly drew parallels with the war in Vietnam, featuring a map of Iraq surrounded by the words, Viet Nam. But historical parallels are always tricky. Seeking to show repeated patterns can make you miss those things that are different and thus require new approaches. In looking at these two movements, I’ll show their similarities but also point out how they differ in ways that may matter to current and future organizing for peace.

Figure 3. No author, 2003. Courtesy of Peace Symbol.org.

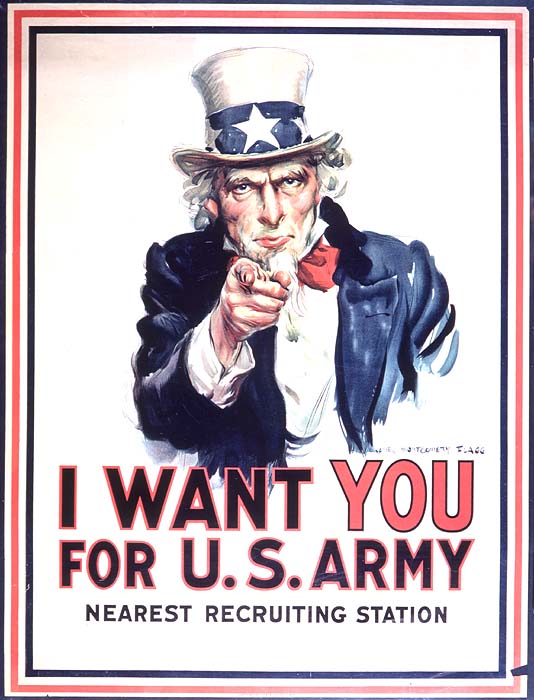

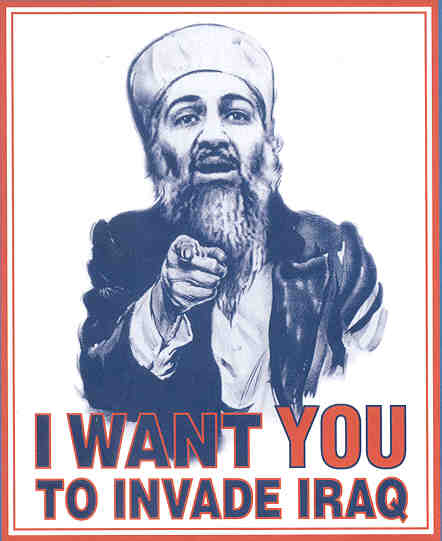

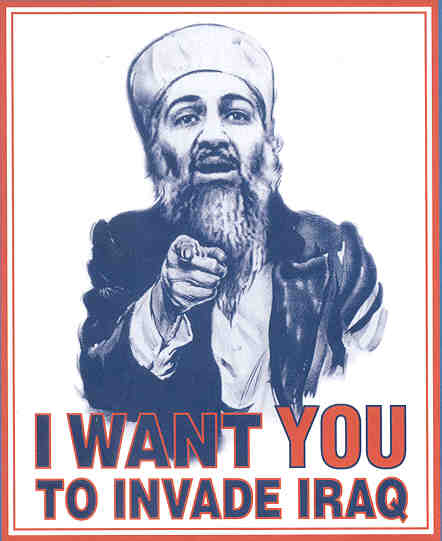

The movement culture form I will use to compare and contrast the peace actions in the protest poster. This is a particularly appropriate choice since the modern protest poster developed in response to war and in the form of the military recruitment poster. Beginning during World War I (or the Great War, as it was known then, since it was advertised as the “war to end all wars”), the recruitment poster became a major part of nation-state propaganda throughout the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. The most famous such poster in the United States is no doubt the “Uncle Sam Wants You” poster designed in 1917 by James Montgomery Flagg (Figure 4). This image has been and continues to be parodied frequently in peace movement posters (Figures 5 and 6), keeping alive the form’s origins in counter-recruitment efforts.

Figure 4. James Montgomery Flagg, 1917. Public domain.

Figure 5. Committee to Help Unsell the War, 1971. Courtesy of Sixties Project.

Figure 6. “I Want You,” 2003. Courtesy of Cyberhumanism.

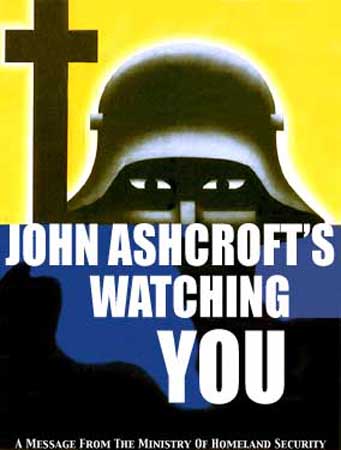

Extending the logic of recycling and improving the Uncle Sam poster, soldier turned artist Micah Wright has created a whole series of “remixed” propaganda posters.1 He updates a World War II poster that helped fuel the anti-Japanese paranoia that led to an executive order that imprisoned more than one hundred thousand citizens of Japanese ancestry. The remix (Figure 7) is directed at former Attorney General John Ashcroft, one of the prime architects of the so-called PATRIOT Act, legislation that like internment indiscriminately stigmatized and negatively impacted the lives of thousands of Arab Americans, Muslims, Middle Easterners, and thought-to-be Middle Easterners in the United States. In the process this unpatriotic act also subverted the privacy of all US citizens. The logic of such open-ended surveillance always tends toward where the protagonist of Bob Dylan's "Talking John Birch Paranoid Blues" arrives -- the investigator ends up even investigating himself.

Figure 7. Micah Wright. Courtesy of the Propaganda Remix Project.

Posters have changed in style, mode of production, and method of distribution over the years, from laboriously handmade silk-screened images stapled to trees to images made and circulated instantaneously across the world by computer. But their basic functions have remained the same. Movement posters are designed, as are the military ones they counter, primarily as recruitment and educational devices. They aim to tell a story quickly, dramatically, and primarily visually. They must condense often quite complex ideas and ideological positions into a few images and words. As with murals (see Art of Protest chapter 4), poster imagery can even speak to audiences of limited literacy. In addition to serving to recruit new members, posters can remind current members of key events and reinforce key ideas. And they can educate people about crucial issues with a few words or images that draw you in because they make you want to know more.

The visual languages of the protest poster derive from many sources. In addition to parodying the military poster, movement posters often use techniques from the art world. Sometimes this is simply the use of certain colors, tones, or styles. The “Make Love, Not War” poster from 1967 (Figure 1) derives, for example, from the “psychedelic” style of the sixties rock concert poster (see Figure 18).

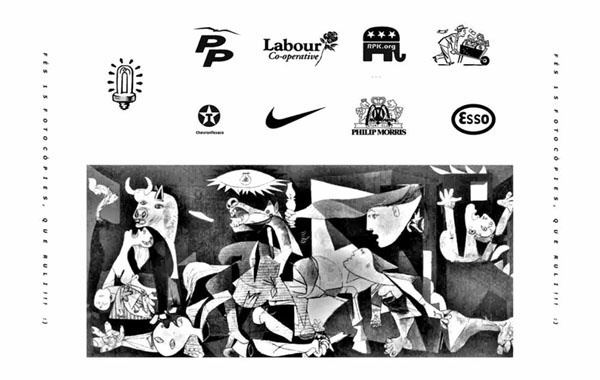

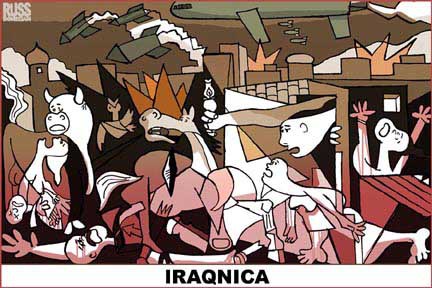

At other times influence from the art world may take the form of recontextualizing a famous artwork. For example, there are many variations of Picasso’s protest painting "Guernca," as in the posters below (Figures 8 and 9). The untitled poster in Figure 8 seeks to link the fascist bombing of the Spanish town for which Picasso’s painting is named to the commercial interests protesters claim lie behind the bombing of Iraq, and to the political needs of the Republican party. The poster may also serve as a reminder that art itself has become a commodity, with works like those of the great anticapitalist Spanish master hanging now on the walls of the very corporations he detested and that peace activists hold responsible for the war system. “Iraqnica” (Figure 9) is more direct in paralleling "Guernica" and Iraq War deaths, evoking for those who know history that in both cases it was civilians, not soldiers, who bore the brunt of the falling bombs.

Figure 8. untitled, by Nowar, circa 2003. Courtesy of Miniature Gigantic.

Figure 9. “Iraqnica,” n.d. Courtesy of Cyberhumanisme.

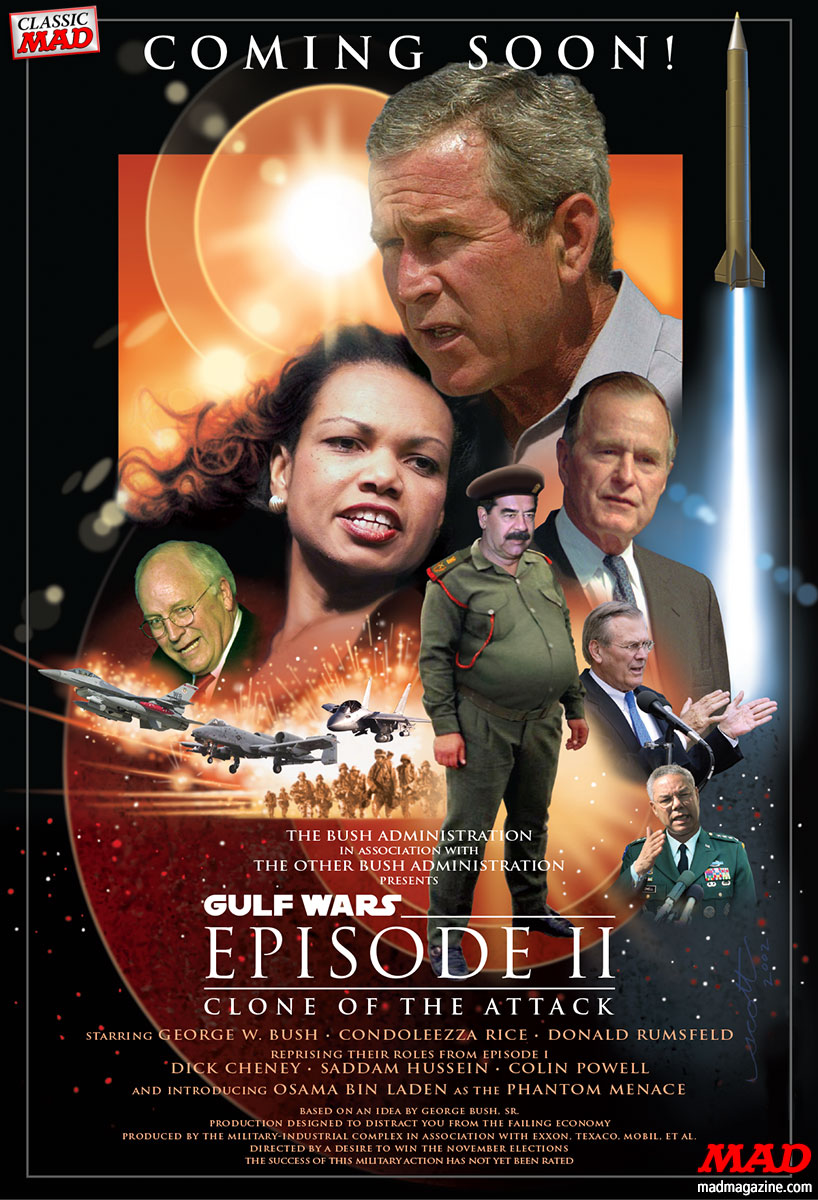

Another often used source for poster inspiration is American popular culture. In both the Vietnam and the Iraq war eras, movie posters proved useful in suggesting the unreality of war to those in power and the way in which wars are produced and consumed like films (Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 10. “Vietnam: An Eastern Theatre Production.” Courtesy of Sixties Project.

Figure 11. “Gulf Wars: Episode II,.” 2002. Courtesy of Mad Magazine.

Parodies of advertising were also popular in both eras, linking the selling of war to the selling of popular products, and the passive consumption of war images with quiescent consumption of consumer goods (Figures 12 and 13). One of the most famous antiwar poster groups of the sixties, the Committee to Help Unsell the War, consisted of professional ad agency artists and writers who committed themselves to using their skills to “unsell” the war rather than to sell products. In another sign of continuity across eras, the group was revived in 2003, and worked to “unsell” the war in Iraq.

Figure 12. “Chanel,” Violet Ray, 1969. Courtesy of Sixties Project.

Figure 13. “Proud Sponsors of War,” n.d. Courtesy of Cyberhumanisme.

While these and other parallels exist in the form and to some degree in the content of antiwar posters, there are significant differences in the two eras. Most important is the ability of contemporary poster-style images to be spread much more rapidly and fully via the World Wide Web. As we will see in our discussion of the movement against the war and occupation of Iraq, the Web has allowed peace movements to compete much more fully with mainstream mass media to disseminate images.2 The Web has become both a “virtual wall” (meme as poster), and a means of disseminating images that can be downloaded and posted the old-fashioned way on trees, walls, fences, billboards, or any other public space.

While peace posters are largely a product of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, peace movements have a much longer history on this continent, preceding even the formation of the United States. The longest running peace effort is that of pacifist churches, including Amish, Mennonites, and Quakers. Among these, the Society of Friends, better known as “Quakers” (originally a derogatory term given them by the Puritans with whom they often tangled during colonial times), have played the most extensive role. The Society of Friends began opposing war in the seventeenth century, focusing initially on white aggression against Native tribes in the Northeast. To this day, the Society of Friends and organizations they have founded, like the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the War Resisters League, remain the backbone of many peace movement efforts in the United States.

Historically, there have been five main, sometimes overlapping, strands of peace movement activism in the U.S. tradition:

1. Moral/religious pacifists opposed to all wars. These include not only the Protestant churches mentioned above but also the radical pacifist Catholic Workers, as well as “philosophical” pacifists who derive their ideas from a variety of secular sources, from Henry David Thoreau to Leo Tolstoy to Mahatma Gandhi to and Martin Luther King Jr.

2. Internationalists opposed to wars based on national chauvinism. These include the American “anti-imperialists” of the 1890s, including figures such as writer Mark Twain, and others who argue for diplomacy rather than war, along with citizen-to-citizen groups who seek to circumvent governments in order to develop personal relationships that belie opposing state ideologies.

3. Feminist peace activists. There is a long tradition of women opposing war as a product of masculinist competition among men. One of the oldest and strongest of the organizations in this tradition is the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), founded in 1919 in the wake of World War I. Other groups following this line of thought include Women Strike for Peace (WSP), founded in 1961 to support nuclear disarmament and later a force in the Vietnam antiwar movement, numerous feminist antiwar groups that emerged amid the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and a strong wave of feminist antimilitarism in the 1980s exemplified by the Women’s Pentagon demonstrations all the way up to the Code Pink activists opposing the invasion and occupation of Iraq.

4. Progressives, socialists, and anarchists who see U.S. wars as tied to corporate influence at home and imperial designs abroad. These folks argue that most wars are not accidents or mistakes or in defense of freedom, but an inevitable outgrowth of economic and political inequalities in the United States and around the globe that can only be addressed by systemic changes in the national and international distribution of wealth and power.

5. Moderates, liberals, and sometimes “isolationist” conservatives who find a particular war ill-conceived, unwinnable, or otherwise strategically unnecessary. This stream is only selectively anti-war, or perhaps strategically so. The are anti- one particular war, while often caught up in other wars. This group often includes johnny-come-lately who oppose a war effort only after it begins to falter.

All five of these strands, in various forms and ideological combinations, are present in both the Vietnam and Iraq eras. In terms of strategy and tactics, moderates, liberals, and their internationalist variants have relied primarily on public education, lobbying public officials, nonconfrontational demonstrations, and independent, often citizen-to-citizen, diplomacy. The more radical progressive forces and pacifists have used all these methods but have added nonviolent civil disobedience and conscientious objection (both sometimes leading to periods of incarceration), and direct action protests aimed to slow down or stop the actual mechanism of recruitment and deployment of soldiers.

U.S. peace movements in the post–World War II period can be divided into four main waves of peace movement activity: the anti–nuclear weapons movement of the 1950s, the anti-Vietnam era of the 1960s and 1970s, the antinuclear and anti-intervention movements of the 1980s, and the movements surrounding U.S. involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. In comparing and contrasting only two of these waves of activism, the Vietnam and Iraq antiwar movements, I will sometimes note the influence of the other two waves of peace action as well. All four waves involved, to one degree or another, interactions between U.S. activists and their peers around the world and drew upon all major strands of peace activism. Liberal and radical forms of pacifism in particular have offered a powerful base and set of tactics to all four waves of peace activity since World War II, and no more so than in the movement against U.S. intervention into the civil war in Vietnam.

Part 1. The Movement(s) against the War in Vietnam

U.S. involvement in the conflict in Vietnam can be traced back to the 1950s when France was the major protagonist in a war against nationalist forces seeking to overthrow French colonial control of the country then known as Indochina. The French efforts were essentially defeated by the late 1950s, and gradually the U.S. presence expanded, moving from CIA agents as “military advisers” to a few full-fledged combat units to thousands of troops. As the U.S. government became more involved, the conflict was portrayed as a major front in a worldwide effort against communism. In contrast, most people inside Vietnam, and many outside, saw the conflict as an anticolonial independence movement that had been turned into a civil war by French and U.S. efforts to back figures they thought would be more pliable than the main Vietnamese leader, Ho Chi Minh (Figure 14). Because these attempts to set up puppet regimes in South Vietnam never gained enough of a foothold to make an internal civil war viable, the U.S. and their allies were the true antagonists of the war.

Figure 14. Rene Medero, 1974. Courtesy of Sixties Project. Ho Chi Minh: “Nothing is more precious than independence and liberty.”

Ho had originally asked for U.S. aid in his independence movement, suggesting that a country founded on an anticolonial Declaration of Independence should be sympathetic to his efforts. But amidst a simplistic Cold War division of the world into good guys and bad guys, the United States decided Ho was a bit too independent to be a good guy. This, and a more sympathetic reception from the Soviet Union, led to the self-fulfilling prophecy of Ho’s alignment with communism, although intended to be an independent Vietnamese form.

The 1960s was as culturally and politically exciting and dynamic as any decade in U.S. history, and the war in Vietnam was at the center of much of the era’s activity. In the early sixties, under President Kennedy, political leaders had begun to debate the U.S. “police action” in Vietnam, but it did not widely register on the American political scene for several more years. By 1964, both the war and an antiwar movement were slowly emerging into public consciousness. As has been the case in much of U.S. history, the peace churches, especially the Society of Friends, were among the first to express opposition to the war. Over the course of the next ten years, the peace movement expanded continuously, to include major youth contingents, some prominent liberal politicians, and eventually a majority of all Americans, as well as most of the rest of the world.

Key developments in the United States included the emergence of a vast “New Left” student movement and a youth counterculture known popularly as "hippies." These new contingents built on and were to a degree stabilized by long-term activists from the pacifist churches and veterans of the antinuclear movements of the 1950s. Indeed, the most famous emblem of the Vietnam War era, the peace symbol, originated as the “Ban the Bomb” logo of Britain’s Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in 1958 (Figure 15).3

Figure 15. Courtesy of the CND archive.

The New Left, Students, and the Rise of the US Peace Movement

No force contributed more to the Vietnam ant-war movement in the sixties than the student-based New Left that sparked and spread like a prairie fire. As the 1950s came to a close, virtually no one predicted the sudden upsurge of radical political and cultural energy. But there was at least one major exception, rebel sociologist C. Wright Mills, who believed he was seeing the emergence of a “new left” in America. As the decade wore on, this claim came to seem prophetic as the civil rights movement was joined by student and peace movements to form what became known as the New Left.

Much of the “old” left” of the 1930s was tied to the U.S. Communist Party USA. In the thirties communism was a mass movement with deep roots in U.S. traditions and U.S. social concerns, and during World War II the Soviet Union was a key U.S. ally. But by the Cold War of the 1950s anyone associated with communism was branded un-American, if not traitorous. Anticommunist hysteria and repression during the McCarthy era of the fifties largely silenced not only Communists but virtually any liberal, progressive, or otherwise dissenting voices. Thousands lost jobs just for being evenindirectly associated with dissenting ideas. Young people soon defied this silencing and took up the challenge of articulating a radically democratic critique of the nation’s failures to live up to its ideals. Later historians would come to see more continuities between the “old left” of the 1930s and the “new” one of the 1960s, but for those riding the emergent wave of activism, “newness” was of great importance in creating a generational identity.

The most important groups to emerge as part of this New Left were the radical civil rights organization the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, see Art of Protest chapter 1) and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), founded in 1962. Both groups took much inspiration from the Civil Rights campaigns of the latter half of the 1950s. SDS’s famous founding document, “The Port Huron Statement,” argued that political repression, the threat of nuclear war, and the consumerist cultural conformism of the fifties had rendered most Americans complacent in the face of their government’s failures to deal with racism, poverty, and the decline of democratic ideals. In place of this quiescence, they called for a “participatory democracy” in which citizens took control over all aspects of their political, economic, and cultural lives. Many early SDS members were veterans of the civil rights movement in the South where they had learned both of the shortcomings of a supposedly just society and how to organize nonviolent direct action campaigns to fight these injustices. They believed idealistically in American democracy and that democracy was far from being fully realized here or elsewhere. SDS argued that America’s ideals were being betrayed by racism, warmongering, and obsession with material wealth.

The New Left became a kind of intellectual/activist core that sparked and helped shape the mass involvement of students in the antiwar and other progressive movements that grew as the sixties wore on. In its first few years, the mostly white SDS focused primarily on issues of racism and poverty in northern U.S. cities. Their eloquent calls for ordinary people to take control of the institutions that shaped their lives played a role in the formation of a variety of poor peoples’ movements and even shaped what Democratic president Lyndon Johnson (1963–68) called his War on Poverty. But the war in Vietnam overtook the War on Poverty, and the former increasingly became the major focal point for SDS, not least because the cost of Vietnam in monetary and human terms was undermining both liberal and radical efforts to fight poverty and other injustices. Johnson called his wider effort a move to create the “Great Society.” But as Figure 16 graphically illustrates, that Great Society was drowned in the blood of Vietnamese and Americans.

Figure 16.Screen Prints, ca. 1967. Courtesy of Sixties Project.

“What’s So Funny ’bout Peace, Love, and Understanding?”: The Counterculture

“Hippies” have now become for many only a kind of cultural joke, a retro style for fashion designers or for kids to wear on Halloween. But in their context, the hippie counterculture played a significant role in the peace movement and the wider process of social change in the 1960s and 1970s. The hippie counterculture contributed especially to the left-pacifist dimensions of the movement. If we examine “hippies” closely as a social text, we can see that their styles, slogans, and ways of being formed a coherent, if not often fully worked out, critique of U.S. politics and culture.4

Hippies acted out a critique of the middle-class, consumption-driven, “organization man” culture of the 1950s that had also been a target of SDS in “The Port Huron Statement.” The counterculture’s critique included a strong rejection of the war system and led to the ubiquitous flashing of the peace sign (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Democratic Convention protest, 1968. Source unknown.

Where the New Left concentrated primarily on analytic critique of the political and economic structures underlying the war system, the hippies attacked it head on as a way of life, or “lifestyle”—a term just emerging at this point that in its very name suggested the superficiality of living as just a style. In a sense, the hippies sought to live out the alternative culture the New Left theorized more than it practiced. Even for those who did not become hippies, the hippie examples of alternative ways to live helped distance young people from their elders who were prosecuting the war. What became known as a “generation gap” got its visual markers (long hair for both genders, colorful clothing, and so on) and its cultural experimentalism (psychedelic drugs, Eastern religions, antimaterialism) from the hippie counterculture. Many young Americans remained conservative during this era, but millions felt a strong generational tie driven by a combination of countercultural and progressive politics. Over the years both tensions between and syntheses of the New Left and the hippies emerged. Both represented a response to deep-seated discontent with the rampant materialism and the empty conformism of much mainstream U.S. culture.

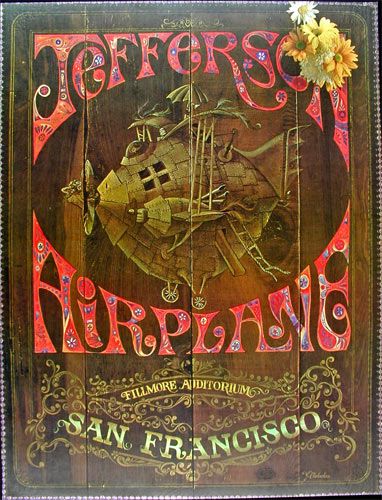

Hippie style entered the antiwar movement and its posters in a variety of ways. Most directly, the psychedelic forms developed to advertise rock concerts were adapted for movement purposes, first through benefit concerts and later through a more general stylistic preference (compare Figure 1 to Figure 18).

Figure 18. Fillmore Auditorium concert poster. Courtesy of Peace Rock.

And psychedelic rock became the sound track of the movement for young people, hippie or not. Where the goal of mainstream America was to make as much money as possible, the goal of hippies was to live on as little as possible and model alternative economics that were not based on endless expansion of consumerism. An embrace of voluntary poverty by middle-class kids, however protected some were by possibilities of going home again, was a powerful living statement about the emptiness of a life of materialism. Hippies drew much of their vocabulary and their costuming from marginalized, oppressed elements of U.S. society, particularly African Americans and Native Americans. Black slang provided most of the base for hippie terminology, mediated in part through the beatnik phenomena of the late 1950s that fed into the hippie scene, particularly in places like San Francisco where the first and strongest wave of the counterculture emerged near the North Beach beat scene.

But if black lingo was important to the mostly white hippie culture, other forms of identification with blacks were difficult in the years of countercultural ascendancy (roughly 1965 to 1969). Blacks (and other people of color) were in search of identities fully separate from white racist America. That search was at the heart of the black power movement then raging (see Art of Protest chapter 2). Given this limitation, hippies identified instead with an even more marginal and much less visible culture, American Indians. Hippie clothing drew heavily on what was imagined to be "Indian" modes. Beaded headbands, deerskin garments, moccasins, and feathers were the most obvious signs of this connection. Hippies actively chose downward class mobility and were often resented by both those in the class above them whom they left behind and those in the lower classes with whom they sought solidarity. Flaunting poverty was more effective as a critique of their middle-class forbears and contemporaries than in aligning with working-class and poor folks, most of whom strove to hide their poverty as they sought to leave it behind. Their embrace of a postmaterialist cultural possibility was more convincing to those who had passed through the materialist moment, who had been satiated with consumer products, than to those who struggled with material deprivation. (A similar credibility gap faced young New Leftists who lived among the poor as they sought to stimulate a participatory democratic revolt of the underprivileged.) Building strong cross-class alliances was and remains difficult for most U.S.-based progressive movements where the "American Dream" continues to seduce many into believing their lives will improve without political change.

Countercultural forms helped give the peace movement a more distinctive style as the look, sound and feel of "freak" culture wove its way into the movement culture, at least for most of the young members. “Peace” as a key word enters the lexicon of hippies from a number of different directions. Most obviously, and most importantly for this chapter, it meant peace as opposed to the war in Vietnam. But in the wider counterculture, as in the wider New Left, it meant peace as opposed to the massive war machine that was U.S. militarism, and militarism was seen as tied to U.S. materialism. Peace also meant peace of mind, as opposed to the mad rush of the nine-to-five, success-obsessed mainstream rat race. As counterculture icon Bob Dylan cryptically put it, “there is no success like failure, and failure is no success at all.”

It is no accident that the freak counterculture emerged between 1965 and 1967, the key years for the emergence of the antiwar movement. The hideous war seemed to expose the twisted logic behind straight society at its most destructive. The counterculture was a peace movement, involving millions of young (mostly white) Americans who saw the roots of war in social conformism, economic materialism, lonely individualism, spiritual deprivation, sexual repression, and deep-seated psychosocial dissatisfaction. Hence it is not surprising that it is the hippie counterculture that gave the peace movement one of its most famous slogans, the one that adorns the poster at the head of this chapter: “Make Love, Not War.” The implication, derived directly or indirectly from psychosocial theorists like Wilhelm Reich and Herbert Marcuse, was that beneath all the justifications for militarism, repressed sexual impulses led to deep frustrations misdirected as hatred of of women and non-whites, political repression of non-conformity, and finally war.

The counterculture increasingly found points of contact with the general movement culture of the antiwar and student movements. The New Left, drawing from the intensely personal experiments of groups like SNCC, had spoken of the “beloved community” and of “prefiguring” the new society within the movement to change it.5

The image of that community had been rather vague, and for some the picture seemed to be developing among hippies. Particularly in places with intense countercultural scenes, like the San Francisco Bay Area, Madison, Wisconsin, and the East Village in New York City, the New Left and counterculture blended significantly. But even there it was sometimes a tense fusion, as from the point of view of many politicos, the hippies were self-indulgent and unorganized, while to the “freaks” the New Left looked too much like a just another bureaucracy of folks postponing life till after the revolution. But whether blended, or marching and dancing in separate groups, the New Left and counterculture formed a very strong base for the youth component of the antiwar movement, and it was youth who drove the movement.

The retro spirit of parody found in hippie clothing, for example, worked its way into antiwar posters and demonstrations. Hippies had a penchant for what would now be called vintage clothing and what might be called anachronistic clothing—Civil War uniforms, nineteenth-century cowboy outfits, and so on—that seem to be a comment on the emptiness of progress defined only in material, not human, terms. One of the most dramatic efforts to make hippies more directly political came in the form of the Yippies, founded by longtime activist Abbie Hoffman. Hoffman and fellow Yippie, Jerry Rubin, sought to direct the countercultural spirit of play and parody right at the heart of the political system.6

Hoffman and Rubin, for example, mocked their felony indictments for their protest activities at the 1968 Democratic convention by showing up in court in uniforms from the revolutionary war of 1776. They were at once reminding folks that those first American revolutionaries were also labeled extremists as well, and at the same time using the inspired comic spirit of the counterculture to point up the drabness of the mainstream system that sought to jail them for committing free speech. A similar spirit was found in efforts during the 1967 antiwar march on the Pentagon, where counterculture activists sought to “exorcise” the demons within the Defense Department complex, and then later tried to levitate the building. While some more serious peace activists decried such actions, for many among the young the point was clear: trying to levitate the Pentagon is no crazier than the war in Vietnam, and a lot less bloody.7

While the merging of hippies and the New Left was not always smooth, at least one observing entity, the FBI, saw their linkage as a serious threat. As part of their viciously repressive counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO for short) against all forces of dissent, the FBI sought to manipulate “mystical symbols” that they seemed to take more seriously than most protesters: “The emergence of the New Left on the American Scene has produced a new phenomenon—a yen for magic. Some leaders of the New Left, its followers, the Hippies and the Yippies, wear beads and amulets. New Left youth involved in anti-Vietnam activity have adopted the Greek letter ‘Omega’ as their symbol. Self-proclaimed yogis have established a following in the New Left movement. Their incantations are a reminder of the chant of the witch doctor. Publicity has been given to the yogis and their mutterings. The news media has referred to it as a ‘mystical renaissance’ and has attributed its growth to the increasing use of LSD and similar drugs. Philadelphia believes the above-described conditions offer an opportunity for use in the counterintelligence field. Specifically, it is suggested that a few select top-echelon leaders of the New Left be subjected to harassment by a series of anonymous messages with a mystical connotation. . . . It is believed that the periodic receipt of anonymous messages, as described above, could cause concern and mental anguish on the part of a ‘hand-picked’ recipient or recipients. Suspicion, distrust, and disruption could follow.”

To my knowledge, there is no evidence that this particular form of mystical psychological warfare had much impact on the movement, though other aspects of COINTELPRO actions did great damage to the New Left, black power, and other radical and liberal groups. On the other hand, the FBI was quite right to sense a connection between the counterculture and the culture of the peace movement. The counterculture provided the sound track—psychedelic rock—as well as much of the costuming and set design for the dramatic confrontations that occurred between pro- and antiwar forces as the sixties wore on.

From Protest to Resistance, 1967–1969

It is no coincidence that the hippie counterculture peaked during the major years of the antiwar movement. Whether addressed directly or obliquely, the war was on the minds of all young people. By 1965, the United States had two hundred thousand troops in Vietnam. The number of troops needed for the war continued to escalate until a draft became the only way to get enough soldiers to fight the war. In response, antidraft activity had by 1966 become the cutting edge of the progressive movement against the war. The draft greatly upped the stakes for millions of young men (women were not subject to the draft at that time) in the United States, with both idealism and self-preservation driving thousands into draft resistance activism. SNCC and SDS stoked the most militant forms of antidraft work, helping to spur new organizations like Resist and The Resistance, both antidraft groups with strong support from the conscientious objector community of radical pacifists. The key slogan of the era was “From Protest to Resistance,” and resistance clearly meant direct action to disrupt any and all aspects of the war machine.

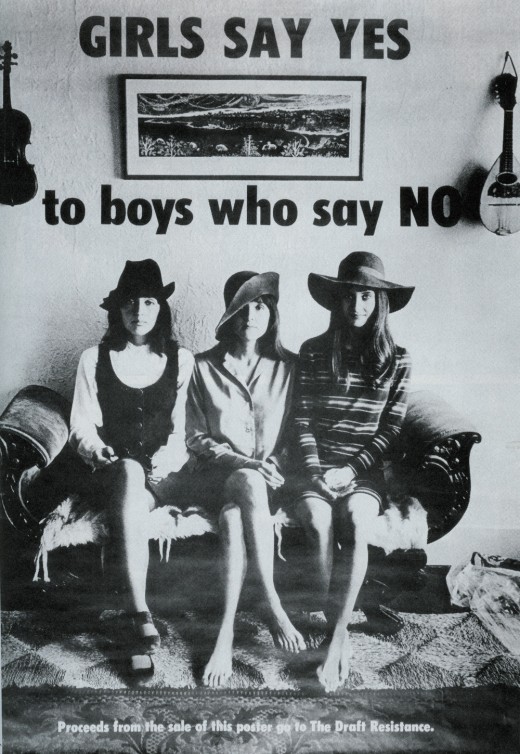

Another, rather more problematic, slogan, “Girls Say Yes to Boys Who Say NO!” also found its way onto a widely circulated poster (Figure 19), featuring famous folksinger Joan Baez and her sisters. I have not seen any data as to whether this reverse form of Lysistrata-ism8 was a significant force in the movement, but an emerging feminist critique of "macho masculinity" as tied to militarism did play a role. And more generally, women in fact played important roles in the draft movement, despite a great deal of sexism. Baez herself made a lifelong commitment to radical pacifism in these years, supporting influential centers for nonviolent study and action such as the still active Resource Center for Nonviolence in Santa Cruz, California. While trivializing and sexist, the slogan offers a backhanded acknowledgment of the crucial roles women played in the peace movement. Despite the sexism endemic in parts of the movement, women were very effective organizers in all the major groups, as well as joining long-standing groups like Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and Women Strike for Peace. More important, the hundreds of feminist groups emerging in the late 1960s and early 1970s offered tremendous energy to the peace forces.

Figure 19. “Girls Say Yes to Boys Who Say NO!” Courtesy of Sixties Project.

The antidraft movement grew rapidly from 1967 to 1969. Actions included individual and collective draft card–burning demonstrations (in one such event more than one thousand young men burned their cards), draft counseling, counter-recruitment for draft resistance and conscientious objection, organizing around and within the military, and direct disruption of draft boards, troop trains, and other elements of the military apparatus. One of the most dramatic of these confrontations occurred as part of a national “Stop the Draft” week in October 1967. At the Oakland, California, military induction center, hundreds of activists, including many vets, shut the center down for hours and engaged in mobile street fighting with the local police over several days (Figure 20).

Figure 20. Vietnam Day Committee, 1967. Courtesy of Sixties Project.

As the war continued, Vietnam veterans became some of the most effective antiwar and antidraft activists, their direct experience of the war’s horrors adding credibility to other critiques. Vietnam Veterans Against the War, cofounded by future presidential candidate John Kerry, was the most widespread and effective of these groups. Each new atrocity in Vietnam brought forth a more militant and radical analysis from the antiwar movement.

The rise of radical ethnic liberation movements, with groups like such as the Black Panthers (see chapter 2), the Chicano Brown Berets, the Asian American Red Guards, and the Red Power American Indian Movement, included elaboration of anticolonial critique that linked so-called U.S. minority groups to Third World struggles that included solidarity with America’s putative enemies in Vietnam. As in these posters from the Black Panthers (Figure 21) and radical Chicano/a activists (Figure 22), Asian American and Native American activists also linked their struggles against racism to what they saw as a racist war in Vietnam:

Figure 21. Emory Douglas, 1970. Courtesy of Sixties Project.

Figure 22. Malaquias Montoya, 1973. Courtesy of Sixties Project.

This Third World internationalism also helped drive white radical antiwar and draft resistance groups toward a more explicit identification of the war as an imperialist effort masked by Cold War anticommunist ideologies (much as folks would later accuse the intervention into Iraq of being a war for oil masked as part of the war on terror). The imperialist argument was several steps further than most white middle-class peaceniks wanted to go in the sixties, and it made their protest seem quite mild and reasonable by contrast.

With each escalation of the violence of the war, there was an escalation of the violence of graphic resistance. Perhaps the most famous poster of this type was “And babies?” done in the wake of the most horrendous event in the war, the My-Lai massacre in which over five hundred men, women, children, and, yes, babies were killed by U.S. troops under the leadership of Lieutenant William Calley.

Figure 23. “And Babies?” Jon Hendricks, Irving Petlin, and Frazier Dougherty, 1969–70. Photo by Ron Haberle. Courtesy of Sixties Project.

Moratorium Time: A General Strike for Peace

By the late 1960s, driven by constant antiwar activity and aided by daily images of war on the nightly television news, many in mainstream America began to believe that the war was a mistake. As with the later war in Iraq, those who saw the war as no mistake, but rather as a conscious part of a larger, devastating policy of intentional imperial militarism, were often frustrated by this more superficial criticism of the war. But the need to stop its horrendous destruction was paramount. Throughout the middle years of the decade, various fragile coalitions with names like the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE, for short) emerged, died, and reemerged as they sought to hold a mass movement together across ideological, class, and racial lines. Those tensions became even more palpable in the late 1960s as tactics became more aggressive, but at the same time the absolute numbers of antiwar forces continued to grow.

The year 1968 was one of the most tumultuous in U.S. (and world) history, with a president driven from office (Johnson declined to run again when faced with antiwar primary candidates in his own Democratic Party), the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, race riots in over onehundred American cities, student strikes on dozens of campuses, a “police riot” at the Democratic convention, and incessant protests against war, racism, and poverty. The exhilaration felt as antiwar candidates McCarthy and Kennedy emerged gave way to despair as the latter was assassinated and the former outmaneuvered for the nomination by business-as-usual candidate Hubert Humphrey. Humphrey’s lackluster campaign led to the election of Republican Richard Nixon, whose “secret plan” to end the war turned out to be a plan to bomb the country into the Stone Age while withdrawing enough U.S. forces to give the appearance of winding down the conflict.

The strategy devised to bring the antiwar movement to a new level of popularity, visibility, and effectiveness was a kind of national general strike known as the Vietnam Moratorium. The idea was brilliantly simple: set aside one day a month as a day to stop all “business as usual” to concentrate on ending the war. The moratorium led to the largest day of antiwar protest to that date. Building on, expanding, and spawning new groups based in various occupations—Computer Professionals Against the War, Teachers Against War, Teamsters for Peace, and so on—the strategy allowed for multiple levels of commitment and a variety of kinds of protest, from the very safe to the dangerously disobedient. While the leaders of various factions continued to squabble, and the gap between moderate, liberal, and radical strands widened, the moratorium idea signaled the rise of a majority-backed movement and propelled a gradual winding down of the war.

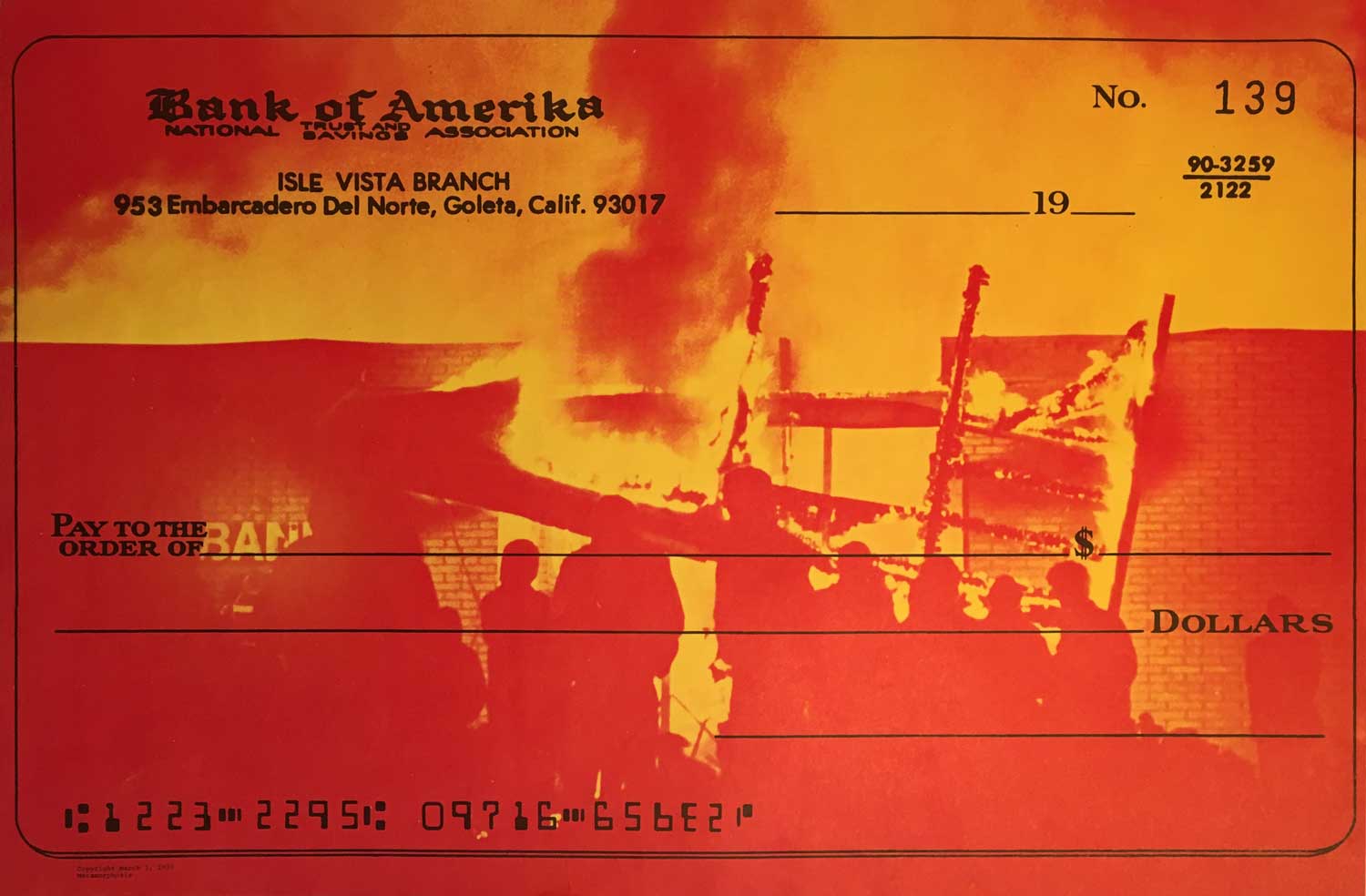

Just as antiwar forces had grown in proportion to the number of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam, the antiwar movement gradually subsided as the troops were slowly withdrawn when and as Nixon claimed he was turning the war over to the South Vietnamese. In fact, Nixon secretly and illegally carried the war over into Cambodia, in a move that helped bring to power the mass murderer Pol Pot.9 The Cambodia incursion led to one of the last major bursts of protest in the spring of 1970, which saw the shooting of unarmed students at Kent State University in Ohio and Jackson State University in Mississippi. The spirit of those protests is captured in “Bank of Amerika Isla Vista Branch” (Figure 24), a parody of a check that pictures the flames rising from the Isle Vista branch of the bank in Santa Barbara, California, which was burned to the ground in protest of the war and the deaths of student protesters.

Figure 24. “Bank of Amerika Isla Vista Branch,” Metamorphosis, 1970. Courtesy of Sixties Project.

Over the next several years the threat of renewed antiwar protests restrained the Nixon administration and forced Nixon and his successor Gerald Ford to actually deescalate the war. While that process took several more years, complicated by the Watergate affair that drove Nixon to resign, the movement had by 1970 made it effectively impossible to expand the war or continue it at the same level. Only winding down remained.

Approximately 3 million Vietnamese men, women, and children died in the war; 58,148 Americans were killed in Vietnam, and another 75,000 were severely disabled. Of those killed, 61 percent were younger than twenty-one. To this day, Vietnam veterans continue to suffer the medical effects of chemicals used in the war, especially napalm and Agent Orange, as well as high levels of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Maya Lin's Vietnam War Memorial eloquently documents the cost in American lives. But no parallel memorial recognizes the millions of Vietnamese who died due to a senseless set of U.S. government policies.

Part 2. The Movement(s) against the War in Iraq

The period between the Vietnam War and the two wars in the Persian Gulf was hardly free of military action on the part of the United States. But it was largely dominated by what became known as the “Vietnam syndrome”: an unwillingness of the United States to use direct military force in the form of armed intervention into another country. Coined by Richard Nixon, who saw it in negative terms as fear to intervene militarily, the syndrome was seen by many as a sign of wisdom and perhaps even the beginning of international justice. However, interventions, such as President Ronald Reagan’s attempts to control the governments of El Salvador and Nicaragua in the 1980s, continued, the intervening years between Vietnam and Iraq were in fact intervention years. although they were conducted more covertly, and without acknowledged direct U.S. military action. After these efforts chipped away at it, the Vietnam syndrome was declared officially dead by President George Bush in 1991 with the Persian Gulf War. However, because that war was short, and had wide support at home and abroad, so it was not a real test of the Vietnam syndrome. The syndrome was not really laid to rest, or so the administration thought, until the invasion of Iraq led by Bush’s son George W. From the point of view of right-wing U.S. policy makers, the economic and political stakes in the Middle East were too high, and the desire for control too total, to allow the Vietnam syndrome to stand. From the point of view of peace activists, however, all this looked like deja vu, calling up not just memories of Vietnam but the massive energies of that antiwar movement.

As with Vietnam, a long colonial legacy is part of any story of the war in Iraq. The country was invented by British colonialism in the early twentieth century. With a long and proud history going back to ancient Mesopotamia, the territory now called Iraq was set up as part of the spoils of war by the British after World War I. After World War II a series of unstable governments in Iraq eventually led to the emergence of a military junta backed by the United States and headed by Saddam Hussein. Over the years Saddam solidified his power and emerged as the dictatorial leader of his country. U.S. policy toward Iraq and the Middle East region generally has been erratic in the extreme, leaving a legacy of extreme distrust. For example, despite Saddam’s well-known torture, abuse, and murder of his own citizens, the United States backed him and provided him weapons in his war in the 1980s with regional rival Iran. The United States provided this support because it viewed fundamentalist Iran as a greater threat than secular Iraq. The weapons and technology the United States gave Saddam are among those being used today against U.S. forces.

One of the most highly educated populations in the Middle East, Iraqis are well aware that self-interest, not an altruistic desire to “spread democracy,” is at the heart of current U.S. policy in their country. The erratic history mentioned above, the vast oil reserves, the commercial possibilities, and the strategic position of Iraq at the heart of the Persian Gulf region are widely understood there as to be the reasons for the invasion and occupation. Gratitude for the ouster of Saddam dissipated quickly when it became clear that the invasion was to be followed by a long occupation. Unlike in Vietnam, the insurgents are not widely popular, because most citizens do not share the religious extremism motivating the anti-U.S. forces. But the insurgents are seen, as in Vietnam, as fighting in part for the country’s independence. That has helped make the occupation a recruitment force for terrorists who previously had little hold in Iraq, given Saddam’s secularism and fear of overthrow by these very forces, partly backed by Saddam’s Iranian enemies (a sentiment represented in yet another parody of the Uncle Sam poster, Figure 25).

Figure 25. No author, 2002. Courtesy of Tom Paine.com and the Florence Fund.

As in Vietnam, the U.S. presence created a civil war where before there had not been one. But the sides in the Iraq internal conflict are far more complicated than in Vietnam. Apart from a few members of the business elite, there is very little backing for the U.S. occupation, but there is considerable fear of an Iranian-style Islamic fundamentalism that could emerge were the insurgents to gain power.

Wars and Peaces

The U.S. war in Iraq generated the largest antiwar movement in the history of the world. Indeed, the New York Times went so far as to declare the wider movement the “world’s second superpower.”10 On February 15, 2003, somewhere between 10 and 20 million people in more than six hundred cities in sixty countries across the globe demonstrated against the then-impending war. This, the largest “focus group” (as G. W. Bush dismissively called it) ever assembled, rested to a great extent on the cyber- and face-to-face networks forged by the movement(s) for global justice (see chapter 9).

The global justice movement (see chapter 9 of Art of Protest) was the backbone of the efforts to end the Iraq war, both in the United States and around the world. While there was initially some concern that a peace movement would distract from larger movement goals,11 calls for resistance to the invasion came quickly from the European Forum and soon thereafter the World Social Forum—the central meeting site of the global movement. The extensive network provided by the global justice movement, along with more specific antiwar discourses and networks arising from earlier opposition to Desert Storm, are the main reasons for the unprecedented fact that a very large antiwar movement grew up in the United States and around the world prior to actual combat.

Figure 26. Five hundred thousand people rally in New York on eve of war, February 15, 2003. Source: “No War on Iraq."

One of the key coalitions active in the United States, United for Peace and Justice (UPJ) bears in its very name (and likewise in its constituent groups) the mark of the globalization movement. The UPJ “peace through justice” coalition is made up of more than thirteen hundred separate organizations whose normal focus is on racism, the environment, gender justice, sustainable agriculture, human rights, health care, and dozens of other issues. But all perceive the war as threatening to the achievement of their social and environmental justice goals. Other important and wide-ranging coalitions include International ANSWER, Not in My Name, and Win Without War. These coalitions are broadly representative of the whole populace, but as in the sixties, students and other young people have played an especially dynamic role. Youth subcultures including neo-hippies and New Agers, punks, riot grrls, ravers, and hip-hop boyz and girlz add flavor to the mix, alongside just plain kids fighting for justice and peace. Again, most of these youth learned their organizing skills in the movement against corporate globalization, and in that movement they learned that the wider the base, the stronger the structure.

While stopping the war proved impossible in the face of a U.S. president contemptuous of the views of anyone beyond his small circle, the sometimes tense coalescence of the antiwar and global peace movement created a strong dynamic whose power has already greatly shaped the U.S. political landscape. Despite Bush’s narrow reelection in November 2004, polls showed that by election time the majority of Americans, joining the rest of the world, believed the war in Iraq to have been a “mistake”—far much too mild a term, certainly, but a far cry from popular U.S. sentiment as the war began, and one measure of the movement’s impact. Compared to the years it took to turn a majority of Americans against the Vietnam War, this is a phenomenal achievement. The percentage of negative responses continued to grow into 2005.

While the U.S. movement against the war in Vietnam only slowly took advantage of its international allies, the peace movement directed against the occupation of Iraq was, thanks largely to the antiglobalization network, international from the beginning. At the World Social Forum, in Mumbai, India, in January 2004, a subgroup held a General Assembly of the Global Anti-war Movement. As the organizational site that most fully legitimates a claim to a single global peace and justice movement, the formation of a separate antiwar assembly suggests that antiwar work is necessary but partial. As activists embedded in a larger structure, these antiwar workers are among those most likely to bring to light the transnational intricacies of struggle in which the evolving movement(s) in the United States will play its particular role. The movement for global justice (see Art of Protest chapter 9) is still the best hope for an alternative to the clash of fundamentalisms among the authoritarians and evangelical crusaders on the right, extreme Zionists in Israel, and jihadi militants like Osama bin Laden whose cause the war has done so much to further.

Antiwar and/or Peace Movements

The U.S. branch of the movement against the occupation of Iraq is formed by two interrelated phenomena: an “antiwar movement” focused specifically on the U.S. intervention and a “peace movement” that is part of the larger set of forces arrayed against “neo-liberal globalization” policies and practices. To chart the relationship between the movement against the Iraqi war and occupation on the one hand, and the movement against corporate globalization on the other, I want to offer a distinction between “anti-war” movements and “peace” movements. I take antiwar movements to be aimed primarily at specific conflicts (Vietnam, Iraq, and so on), while peace movements, which continue and sometimes thrive even in the doldrums between wars (though there have been few such times in recent decades), have a wider agenda—they seek not just to end a particular conflict but to establish conditions that will forestall future conflicts. The Vietnam era had both these components, but they are even more fully developed in the current era.12

The antiwar movement is at once broader and narrower than the peace movement. It is broader because the range of positions opposed to this particular war and occupation force run the gamut, as in the opposition to the Vietnam War, from reactionary isolationists to cautious conservatives to moderates and liberals opposed to unilateralism or “pre-emptive war” to radical pacifists and leftists. Not all of these constituencies are inherently interested in “peace” as a lasting, long-term possibility resting on significant social change. Alongside this “big tent” breadth, there is a narrowness to the antiwar movement when contrasted to a peace movement that grows out of a full analysis of global inequalities at the roots of war. Yet at least some in each of the varied antiwar constituencies may contribute to a more sustained peace movement, and each is certainly important to the more immediate task of restraining preemptive U.S. power.

"No Blood For Oil"

While, given these complex constituencies, the amount and range of Iraq war posters is vast, many of the major themes of the antiwar/peace movement cluster in five areas: “weapons of mass deception” (i.e., war as reality TV or corporate ad campaign); the sexual politics of war; the clash of fundamentalisms; war as tied to domestic policy, clashes over patriotism, and American values; and, most ubiquitously, the politics of oil. As we will see, these themes are often woven together in a single poster.

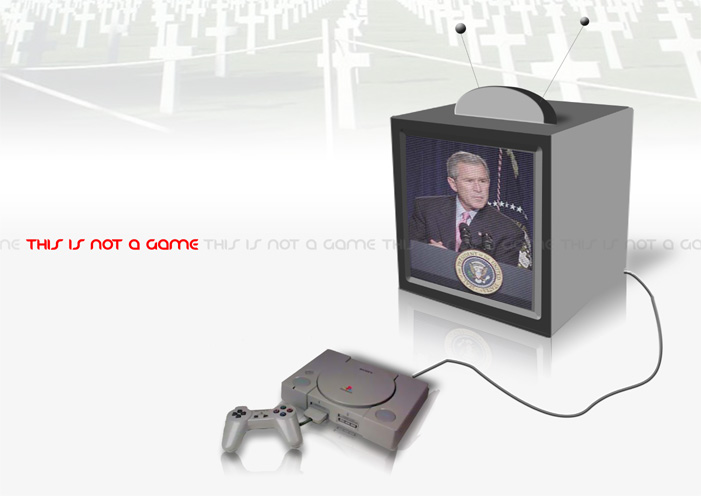

The Bush administration’s most often cited rationale for the war in Iraq was of course the claim that Saddam had developed “weapons of mass destruction.” Massive evidence now shows that to have been completely untrue, and much evidence suggests the administration knew it to be untrue from the beginning of the Iraq campaign. Both the selling of this pretext and attempts to distract from it when its falseness became clear have been a major focus of antiwar posters. In addition to the parody movie poster genre cited above (Figure 109), virtually all other forms of popular culture, from video games to television news, have been challenged for their complicity in selling the war. Figure 27, for example, ties the war to the pervasive computer and video war games that not only desensitize us to killing but are even being used now by military recruiters to ease the transition between war games and the “game” of war.13

“These Are Not Special Effects” (Figure 28) comes at this dynamic from another direction, underscoring the way in which the media reinforces the unreality of war through its dramatic “coverage” —a word that inadvertently suggests that the truth is covered up more than it is revealed by TV “news.” The first Gulf War introduced a camera-tipped missile that allowed viewers to feel like they were guiding weapons of mass destruction down upon Iraq. It was in fact, as the poster suggests, as fake as "special effect," a new level of vicarious war involvement, a dynamic captured in the lyrics to the rock band Metric's song: "Succexy":

All we do is talk, sit, switch screens

As the homeland plans enemies

Invasion's so succexy

Passive attraction, programmed reaction

Passive attraction, programmed reaction

Action distraction, more information.

Figure 27.“This Is Not a Game,” Dara Gill, circa 2003. Courtesy of Miniature Gigantic.

Figure 28. “These Are Not Special Effects,” Vurt, n.d. Courtesy of Miniature Gigantic.

Another pervasive dimension of popular culture, advertising, has also been much parodied by antiwar posters. The themes are usually of one of two types: the war as “sponsored” by corporations with a profit motive (Figure 29), including but beyond oil (the Middle East is a largely untapped market region for U.S. multinationals), or commercialism as a ubiquitous distraction from the realities of war (Figure 30). The poster “Freedom Fries” both lampoons the petty attempt to boycott all things French because France opposed the U.S. intervention, and suggests that the arms industry has become as normalized as the fast food industry and as widespread as McDonald’s franchises. Indeed, in many of the wars around the world, including Iraq, all sides are fighting with weapons originating in the United States.

Figure 29. “Logo Tank,” n.d. Courtesy of Cyberhumanisme.

Figure 30. “Freedom Fries,” Angel Vazquez, circa 2003. Courtesy of Miniature Gigantic.

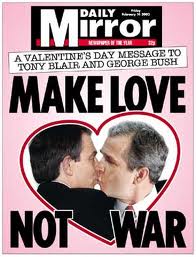

The sexual politics of the war have been approached in a number of different ways, but perhaps most commonly in the mode of a “boys and their toys” critique of the masculinism that finds war more manly than diplomacy, drawn largely from the long history of feminist antimilitarism. A number of posters have taken this logic a step further, by finding a homoerotic subtext in the male bonding around the war. To revisit the variation on the “Make Love Not War” theme at the beginning of this essay (Figure 2), Figure 31 suggests that the political strange bedfellows, conservative George Bush and liberal Tony Blair, might get the erotic thrill of their manly mutual pursuits by a more direct means.

Figure 31. Bush Blair kiss. N.d. Courtesy of Le doigt.

Issues of religious fundamentalism and gender politics have also been tied together in posters. An argument honed in the Afghanistan campaign and transferred to Iraq was the notion that the United States was fighting to save Middle Eastern women from oppressive religious traditions like the wearing of veils and the burka. Not lost on U.S. activists was the irony of an antifeminist promoter of Christian religious patriarchy defending Afghan and Iraqi women. Less obvious, perhaps, was the fact that actually existing feminist groups within Afghanistan and Iraq condemned the U.S. presence there and had a very different notion of how to liberate the women of those countries, one that included recognition that veils, burkas, and other religious attire had many different meanings in differing contexts. The women of RAWA (Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan), for example, the main feminist organization in country since 1977, fought the Taliban for years before the U.S. intervened, and now fight the U.S.-imposed regime. They have criticized the religious intolerance and hypocrisy of the military occupation while maintaining their own secular version of women’s rights and full democracy. The racist assumption that all Arabs are alike also veils the fact that under Saddam’s hideous but secular regime women were not required to wear religious attire and that Iraq has a long history of highly educated and professionally active women.

The poster in Figure 32 offers a complex set of comments on this pretext of fighting Islamic fundamentalism that was another of the many, shifting rationales for going to war.

Figure 32. “Free Market Fundamentalism,” Leon Kuhn, 2003. Courtesy of Leon Kuhn.

In addition to mocking G. W. Bush’s concern for Middle Eastern women, this poster juxtaposes the supposed problem with its proposed military solution, and unveils that solution as bringing not “freedom” but the free market to Iraq and the U.S. corporations who would benefit from that limited version of freedom. Domestic U.S. politics and a struggle over “American values” figure into the war poster in a number of different ways beyond the question of corporate profits. Perhaps most common are attacks on U.S. freedoms rationalized as part of the war on terror, and a parallel claim that to question these limitations on freedom in the United States is to be unpatriotic. In “Democracy Threat” (Figure 33), this takes the form of at once parodying the color-coded terrorist threat system, which many activists see as a means to frighten the U.S. populace into embracing Bush, and the ironic threat to U.S. democracy posed by the crusade to “bring democracy” to the Middle East. “Got Democracy?” (Figure 34) takes this issue on more directly through another key word much used in Iraq, “democracy”; how, it asks, is torturing Iraqis going to endear people to promote a U.S. version of democracy? “The American Way” (Figure 35) uses six simple words and a crayon to make a parallel argument that American values have been reduced to American military power.

Figure 33. “Democracy Threat,” Fact Shirt, n.d. Courtesy of Fact Shirt.com.

Figure 34. “Got Democracy”? Robert Anderson, Zachary Anderson, and Mark Gettys, n.d. Courtesy of Another Poster for Peace.

Figure 35. “The American Way,” Adam Faja, n.d. Courtesy of Miniature Gigantic.

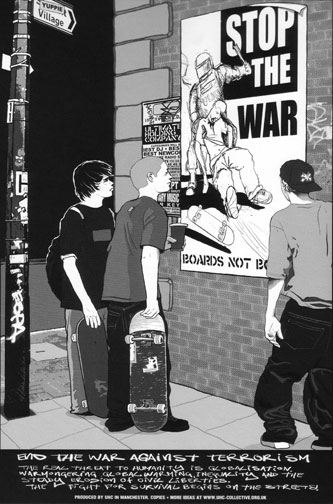

“Skate Poster” (Figure 36) is a uniquely self-referring poster showing young skateboarders looking at an antiwar poster. The poster depicts police brutalizing a protester, rather than a scene from the war, and includes in some versions text from the antiglobalization movement linking peace to questions of justice. It also seems to play on youthful bravado in the face of authority to challenge the dominant war story told by the White House.

Figure 36. “Skate Poster,” Jai Redman, n.d. Courtesy of UHC Collective.

“No Child Left Behind” (Figure 37) approaches domestic policy in a different way. It shifts the meaning of Bush’s famous slogan about school curricula and offers a subtext pitting declining funding for education in the United States to the costs, both human and financial, of the war. “From the Poverty Line to the Front Line” (Figure 38) attacks this issue from a different angle by referencing what some call the “poverty draft”—the fact that our volunteer military is often the only job option for poor and low-income folks in the society.

Figure 37. “No Child Left Behind,” Mike Flugennock, n.d. Courtesy of Mike Flugennock.

Figure 38. “From the Poverty Line to the Front Line,” Committee to Help Unsell the War, 2003. Courtesy of the Committee to Help Unsell the War.

No doubt the most famous slogan emerging out of the two U.S. wars in the Persian Gulf has been “No Blood for Oil.” The slogan in fact was born during the first Persian Gulf War but much more effectively recycled during the war in and occupation of Iraq. While the slogan is strikingly straightforward and seems simplistic, it can encapsulate a very complex analysis, as the many different ways in which the slogan has been incorporated into posters reveals. The much-repeated slogan takes on very different nuances depending both on the national or local context in which it is used and on the larger symbolic context of particular posters.14 Its obvious reference to the vast oil reserves in Iraq, for example, is augmented in many posters with words and images arguing that Iraq is not just only a site for oil exploitation but also a strategic space from which the United States hopes to control the flow not just of oil but of political influence over the entire Middle East: oil not just to power our vehicles but and to power politics.

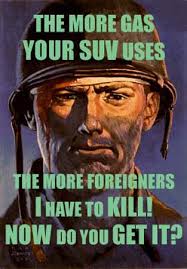

However, the relation to the huge consumption of petroleum in the United States hardly ignored. Another of Micah Wright’s remixed recruitment posters (Figure 39), for example, asks, is your SUV worth it the price of war. Note that it uses a WWII GI image to contrast the "good war" with the won being fought for nothing more than cheaper oil. And the other side of the battle line is evoked, along with the question of so-called collateral damage (killing innocent civilians), through this image of an Iraqi boy with the gas nozzle held to his head like a gun (Figure 40).

Figure 39. Micah Wright. Courtesy of the Propaganda Remix Project.

Figure 40. “End the War,” n.d. Courtesy of Fermiamo la Guerra.

An variation on the no blood for oil poster (Figure 41), offers a rich yet simple image that ties together themes of profiteering, media unreality, and the human costs of war: a gas pump that looks a lot like a television screen, a nozzle transformed into a gun, and a blood red message (fill her up) that links sexual violence to war.

Figure 41. Michael Redding. Courtesy of Miniature Gigantic.

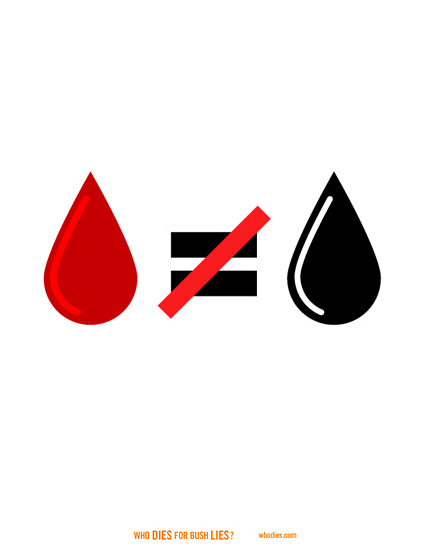

Eventually the best-known slogan becomes so well-known that it can be pared down to stark, wordless eloquence that continues to speak in the face of ongoing violence and deception and for continued efforts to bring peace through justice to the Middle East (Figure 42).

Figure 42. The Committee to Help Unsell the War, n.d. Courtesy of Who Dies.

The End?

In the twenty-first century, posters are more important than ever to antiwar/peace movements. They also, however, face more difficult obstacles than ever in getting their messages across. And both the importance and the difficulties stem from the same source: the increasingly media-saturated, image-and-sound-bite culture in the United States and around much of the globe. The visual power and sound-bite-sized written texts of posters mean they are well-suited to this mass-mediated environment. But the intensive and extensive proliferation of images and sound bites via advertising, television, and the Internet has created a field where antiwar posters face massive amounts of competition in their battle to win the attention, let alone the hearts and minds, of the public.

The peace movement directed against the war in Vietnam began when the number of television networks could be counted on one hand. The first televised presidential debates—Kennedy versus Nixon—occurred only a few years before the movement began, and Vietnam itself was the first war watched on television in homes. That meant that the rules of coverage of both the war and the antiwar movement had not yet been fully set.15

By contrast, by the time of the war in Iraq, five hundred television channels, plus billions of Internet sites, were available. This plethora of information, however, needs to be set against growing sophistication of presidential administrations in “handling” the media and directing their own war show. The invention of “embedded” reporters during the Iraq invasion is only the most obvious of many efforts to shape what was and was not reported during the war. Embeddedness gave the illusion of direct coverage but was designed, and for the most part served, to allow viewers to see only one side of the conflict. Virtually all images of enemy casualties, especially civilians killed by so-called collateral damage, were omitted in order to emphasize the humanity of U.S. forces while keeping the enemy abstract and distanced.

In such a context, posters played a crucial role in trying to bring the face of Iraqis into focus, as, for example, in Figures 37 and 40. These counter-images and sound bites are essential in the face of the omissions in administration and mainstream press images and sound bites. The differences in eras and in wars are apparent also in the far greater number of parodies and media-related posters in the contemporary period. While as noted at the beginning, movie poster parodies and parody ads occurred in both periods, they are much more prevalent in the Iraq war era. This is clearly a response to the more intense media environment and the need to critique other media sources in order to get antiwar messages across. As the first televised war, Vietnam was a far more directly real experience than was the war in Iraq, coming as the latter did in the era of deeply unreal “reality television” and of audiences saturated with various kinds of mass-mediated violence—not only television and movies, but also video and computer games and the World Wide Web.

But if this twenty-first-century environment presents peace movements with a tough space in which to get their messages across, it also presents far more venues for post(er)ing messages than ever before. The speed with which words and images can be spread through a host of communication outlets around the globe helps account for the much more rapid growth of the Iraq antiwar movement. While contemporary activists are deeply frustrated that they were unable to head off the invasion and have as yet been unable to end the occupation, comparison with the Vietnam War era is illuminating in this regard as well. This is all the more remarkable given that the situation in Iraq in many ways contains more ambiguities than did the war in Indochina. Most important, the initial enemy, Saddam Hussain, was an utterly irredeemable figure far different from the nationalist hero of Vietnam, Ho Chih Minh. Similarly, the forces arrayed against the United States were far more united in Vietnam than in Iraq. While almost no one, apart from a view businessmen and politicians who stand to gain directly from U.S. influence in Iraq, still justify the war, the reasons are far more complicated. Still, all the rest of the world apart from Israel, and by 2005 including a majority of U.S. citizens, came to see the American presence there as a mistake.16

In unprecedented fashion, a massive antiwar movement rose before the first bombs were dropped and shots were fired. This is an extremely encouraging thing. That it could nevertheless be dismissed "a focus group" by an administration deluded into thinking it could "win" the war quickly, is not encouraging. But it took more than six years into the Vietnam conflict before the majority U.S. public opinion turned against the war, but that majority viewpoint was achieved less than two years into the Iraq conflict. Clearly, posters and other mediated messages did find a way through the fog of pro-war sound bites, despite an image war waged far more effectively by administration public relations managers. This is cold comfort to the dead and dying, but it is also cause for hope. In Vietnam, close to 50,000 U.S. soldiers had died before most Americans saw the futility of the war, as opposed to 1,500 deaths by the time majority opinion turned against the Iraq occupation.

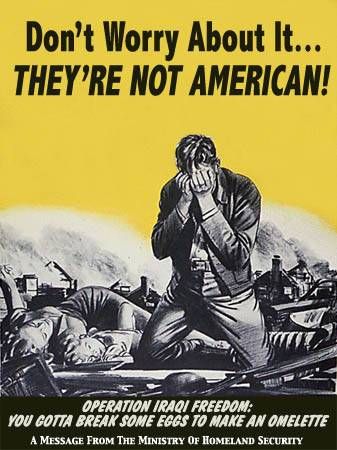

By 1965, roughly two years into the Vietnam War, about 1,800 U.S. soldiers had died. In the following year,casualties tripled, then doubled again the next year, then returned to the previous level, accounting for the bulk of the 58,000 Americans killed. Two years into the war in Iraq, U.S. casualties stood at about 1,700. Whether because of the ongoing impact of the "Vietnam Syndrome," the faster impact of anti-war movements, or military exigences, the exponential growth of US casualties did not follow the Indochina pattern. The same cannot be said, however, for the toll on Iraq civilians who died by the hundreds of thousands. And our final poster suggests those deaths were callously devalued compared to the lives of US soldiers (Figure 43).

By the second decade of the 21st century, there was almost universal agreement, among right and left, Republicans and Democrats alike (excepting some of the politicians like Dick Cheney who most strongly pushed the war) that the Iraq War had been a disaster, started under false pretenses (those non-existent weapons of mass destruction) and pouring accelerant on Mid-East terrorism. It will be up to the next generation of activists and policy makers to develop an "Iraq/Afghanistan Syndrome" that is much more effective than the "Vietnam Syndrome" if we are to head off more disastrously misguided future wars. That will take more artful protest and a major "regime change" in the U.S. government.

Endnotes

1 Wright has created a vast collection of what he calls “remixed” posters, based on World War I and World War II propaganda posters but improved. He has gathered these images in book form as You Back the Attack! We’ll Bomb Who We Want (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003).

2 See Roger C. Peace III, A Just and Lasting Peace: The U.S. Peace Movement from the Cold War to Desert Storm (Chicago: Noble Press, 1991), 28–29, for a similar analysis. To get a sense of another art-based reaction to the war related to posters, see, for example, the over three hundred paintings about the war on the fine art america site at [https://fineartamerica.com/art/paintings/iraq+war].

3 The peace symbol was created in 1958 by Gerald Holtom for the Campaign for National Disarmament in Great Britain, one of the key organizations in early efforts to stop nuclear proliferation.

4 Throughout this section I draw heavily on Stuart Hall, “The Hippies: An American Moment,” in Student Power, ed. Julian Nagel (London: Merlin Press, 1969), a piece that remains one of the finest analyses ever offered of the political import of hippies.

5 For an insider's account of the Yippies, see Hoffman's autobiography, Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture (Nashville, TN: Perigree, 1980).

6 The best analysis of this dimension of New Left theory and practice can be found in Wini Breines, Community and Organizing in the New Left, 1962–1970: The Great Refusal (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1989). See also David Graeber, Direct Action: An Ethnography, Oakland: AK Press, 2009, and Francesca Polletta, Freedom is an Endless Meeting Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2002.

7 The classic account of this march is Norman Mailer’s nonfiction novel Armies of the Night (New York: Signet, 1968).

8 Lysistrata is the eponymous heroine of a play by classical Greek dramatist Aristophanes. In an early form of creative antiwar activism, she organizes the women of several Greek cities to refuse sexual relations with their husbands and lovers unless they abstain from war. Spike Lee's 2015 film "Chi-Raq" potrays Black women recirculating this strategy to subvert the violence of the inner cities and the War in Iraq.

9 The story of the devastating impact of U.S. incursions into Cambodia is detailed in William Shawcross, Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon, and the Destruction of Cambodia (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979).

10 Patrick Tyler, New York Times, February 17, 2003.

11 See Nacha Cattan, “Anti-Globalization Movement Split on War,” Forward (October 12, 2001): 6.

12 My distinction might well be compared to Johann Galtung’s influential discussion of the difference between “negative peace” (the absence of war) and “positive peace” (peace based on sustainable justice, including elimination of the “structural violence” of poverty as well as domestic violence, in addition and as part of ending armed military conflict).

13 See, for example, the Army’s popular game "America’s Army: The Official Video Game of the U.S. Army."

14 Much of my analysis in this section has been made possible by the rich collection of posters on the Iraq war, Peace Signs: The Anti-war Movement Illustrated, ed. James Mann (Zurich: Edition Olms, 2004). My chapter title is also inspired by (or stolen from?) their book title.

15 Daniel C. Hallin, The “Uncensored War”: The Media and Vietnam (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), offers a good survey of war coverage. The classic treatment of media coverage of the social movements of the sixties is Todd Gitlin, The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003 [1980]).

16 Polling data from a variety of major sources as early as May 2005 included the following: 64 percent “disapprove” of Bush’s handling of the occupation; 51 percent say the war was a “mistake”; 57 percent say it was “not worth going to war”; 50 percent believe the Bush administration “deliberately misled” the country into war via the false issue of “weapons of mass destruction”; and only 6 percent think the war was “going well” as of that date. The percentage of those seeing the war in a negative light has continued to rise ever since, to the point where by 2019 seemingly only persons directly responsible for the war like Vice President Dick Cheney were willing to defend it. See pollingreport.com, visited May 31, 2005.